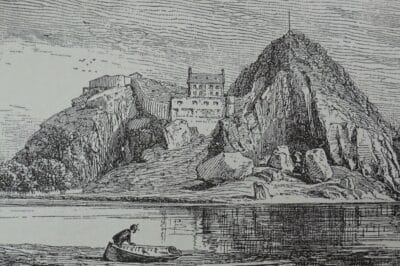

Dumbarton Castle

Dumbarton Castle sits high on a volcanic rock overlooking the junction of the Rivers Leven and Clyde.

Dumbarton Castle, today a Historic Environment Scotland property, may have been Alt Clut (‘Rock of the Clyde’) or Alcluith mentioned by the Venerable Bede.

Perched on top of the Castle Rock it once stood at the heart of the ancient kingdom of Strathclyde one of a patchwork of competing kingdoms that rose before declining in what was a volatile and constantly changing political landscape.

In Gaelic it was “Dun Breatann” or fortress of the Britons. The nearby town of Dumbarton took its name from this term .

Venerable Bede

Serious students of the Rock’s early history might well turn to the Venerable Bede for guidance.

Born in 673 he was a priest, scholar, teacher and writer who lived most of his life in quiet seclusion in the monasteries of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow in the north east of England.

The life’s work of such a man deserves a more intimate examination.

His writing, which ranged from historical critiques to Biblical interpretation and moral criticism is recognised as a major and invaluable primary source of information on much of ancient England and Scotland.

Alcluith

Certainly his reference to Alcluith in his History of the English Church and People, AD 731 was an important recognition of its place in the ever-changing political structure of the day.

Bede noted that…

“…there is up to the present a strongly defended political center of the Britons called Alcluith… and they metamorphosed that rock into a country, where they raised up a kingdom and created kings…”

Venerable Bede

St Patrick

The earliest mention of the Rock is dated to around AD 450 when St Patrick wrote to Coroticus of Alcluith, King of Strathclyde condemning him for, taking slaves after a raid on some of his Irish converts.

However, in the words of Historic Environment Scotland (HES) this story is assigned to “seventh century tradition’ although other respected scholars take different views on this matter.

HES’s reference to tradition may have been influenced by the content of the Book of Armagh and the writing of antiquarian and Church of Ireland Bishop Dr William Reeves (1815-1892), the last private keeper of the manuscript.

The Book of Armagh, today securely housed in the library of Trinity College in Dublin, was almost certainly written (in part) about AD 807 by the “learned and accomplished” Ferdomnach of Armagh.

Other sections of this, small quarto, vellum manuscript are transcripts of much earlier documents.

For scholars with an interest in St Patrick’s life and connection with Strathclyde, this Irish manuscript is of inestimable value.

For example an examination of its pages highlights a number of key areas, without doubt the “Epistle to Coroticus” and the location of St Patrick’s birthplace are paramount.

Reeves argued that portions of the book were genuine but said of St Patrick’s letter to Coroticus that parts, “were said to be spurious.”

As to his birthplace, St Patrick wrote in his Confessio that his father had a house at Bonavem Taberniae thought by many scholars to be in Strathclyde. However others disagree and cite Wales or France as its location.

Whatever the truth about his birthplace, it is not disputed that he was taken to Ireland as a slave at the age of 16.

Although St Patrick is arguably Ireland’s most famous person and might well have a connection with Strathclyde, it’s been an impossible task for historians to untangle the reality from the myth.

Annals of Ulster

Despite its lofty and seemingly unassailable position, the castle was a constant target for those determined to gain a strategic advantage in the region.

Its first recorded fall, tentatively dated to AD 756, was to a combined force of Picts and Northumbrians, under Eadberct and Angus mac Fergus.

Victory celebrations however were understandably brief as the Rock once again changed hands within days.

The Annals of Ulster record a “burning” of Dumbarton in 780 and a later siege described by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) as Hiberno-Norse and dated to AD 871-872.

Strathclyde

That Strathclyde had good reason to be wary of Scandinavian aggression is not in doubt, for Alcluith had, according to the Annals of Ulster, fallen to Olaf the White and Ivar Beinlaus the “two kings of the Norsemen” (two rulers of Dublin) in 870.

The Annals say that after a four-month siege, “they destroyed and plundered it.” Records also note that the Viking raiders, “carried off all the riches that were within it and afterward a great host of prisoners were brought into captivity.

It was the tenth century before the Kingdom of Strathclyde recovered from this onslaught.

In the absence of many surviving primary documents relating to the development of Alcluith, it’s certainly worth pausing to consider some of the findings of an archaeological exploration of the Rock in 1974 and 1975.

On the eastern spur of the Rock, traces were found of a timber and rubble rampart, which had been burned and partially vitrified, an exciting find that Leslie Alcock, Professor of Archaeology at Glasgow University argued, could be linked to the above-mentioned AD 780 conflagration or the later Hiberno-Norse siege.

Within the remains of the rampart, a “Norse lead weight decorated with a glass bangle fragment of Lagore type and an iron sword pommel with Irish parallels were found.

Considering this and other indications of Dark Age life Professor Alcock said that, “the rampart itself probably formed part of [the Venerable] Bede’s civitas Brettonum munitissima [political center of the Britons].

Other early material found included a scattering of Romano-British and Dark Age pottery and glass.

Sadly in some of the additional trenches that were explored, detritus from the British Army who manned the anti-aircraft batteries in World War Two obscured earlier remains.

Some confirmation of the Medieval occupation, in the shape of a silver pendant cross (late 13th or 14th century) and a number of silver coins dating to the reign of Edward I, 1272 –1307 were also found

Dumbarton Castle founding charter

Dumbarton was made a free burgh by Alexander II in 1222, its Rock with its “new castle” was mentioned in the foundation charter.

With Norse control of some of the islands to the west, the castle was of major strategic importance and remained so until their defeat at the Battle of Largs in 1263 and the subsequent Treaty of Perth signed three years later.

During the late 13th and early 14th centuries a number of ‘traditions’ were established at the castle.

It became a royal refuge, a transit point for safer shores, and notably, it became a place of incarceration for men taken in the many conflicts and political intrigues that unfolded over the following centuries.

In 1297 for example, the first recorded prisoners were confined to the castle following William Wallace’s famous victory over English forces at Stirling Bridge.

Although much is known about Wallace’s fortunes after Stirling Bridge, whether or not he was held in Dumbarton Castle before his transportation to London for execution remains a matter of speculation.

Certainly, there was a connection between Wallace and Sir John Menteith the Governor of the castle, the man widely believed to be responsible for William Wallace’s capture in 1305.

The castle’s Wallace Tower, built around 1500 but subsequently demolished when the old north entry was closed in 1795, is thought to be named after him.

Dumbarton Castle and Troublesome Malcontents

James VI (I of England) also found the castle useful for locking up some of the country’s troublesome malcontents. Among them were the Earl of Morton in 1581 and Archibald MacDonald of Gigha in 1605.

Additionally, Patrick Stewart, second Earl of Orkney, one of Scotland’s most unpleasant historical characters ‘resided’ between 1612 and 1614 before losing his head to the swing of the Edinburgh executioner’s axe in 1615.

Napoleonic Wars

Following the 1745 Rebellion, Jacobite prisoners were held there and later the castle’s French Prison, built around 1770, housed more prisoners taken in the Napoleonic Wars.

Dumbarton Castle: staging post

The castle was cold, damp and exposed to Scotland’s west coast gales, it wasn’t the most comfortable of residences yet it became an important staging post for a number of royal visitors.

Testimony in 1634, from castle governor Sir John Maxwell of Pollock, provided some corroboration of the grim and depressing living conditions.

Bemoaning the fact that the hall was not water-fast and that the barns and stables were ruinous and the walls of the Nether Bailey so rotten that they could not, “hold out beasts, let be men.” He declared, “No honest man could dwell within.”

It seems likely that the same miserable conditions existed three centuries earlier when in 1333 following the Scottish defeat to Edward III at Halidon Hill near Berwick the young Scottish king David II was brought to Dumbarton for his security.

A century later (1435) the 11-year-old Margaret, daughter of James I of Scotland left the relative safety of the castle aboard a vessel bound for France and an unhappy and short-lived marriage to Louis XI.

By 1547 a catastrophic Scottish defeat at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh (close to Edinburgh) was a conflict that marked a turning point in the country.

Related articles

- Doune Castle

- Tantallon Castle

- Urquhart Castle

- Dunnottar Castle

- Huntingtower Castle

- 11 Castles in Edinburgh and nearby

Pinkie was the last throw of the dice in Henry VIII’s Rough Wooing campaign, an attempt to force the young Mary Queen of Scots into marriage with his son Edward.

Although Henry had died in the January of that year, England’s Regent the Duke of Somerset continued the fight.

Although victorious at Pinkie he was unable to force the marriage between Mary and Edward.

Earl of Arran

It was to the French that Scotland’s Regent, the Earl of Arran turned to, and Mary, a mere pawn in the ongoing political machinations, was promised to Francis, son of Henry II and heir to the French throne.

In the summer of 1548 Mary, aged only five, made a tearful departure from Dumbarton Castle.

She was accompanied by her two royal half brothers Robert and John Stewart, her guardian Lord Erskine snd her governess.

Her companions the ‘Four Maries’: Mary Fleming, Mary Beaton, Mary Livingston and Mary Seton joined her on the journey too.

West coast Dumbarton was an ideal exit point for her although it was a significantly longer voyage it was considered to be less likely that the French galleys would be intercepted by Somerset.

By 1561, Mary, now widowed, returned to Scotland, visiting Dumbarton Castle for the final time in 1563.

Such are the extensive records of her life we know that she dined there on, “salmon and other sea fish, eggs and white wine.”

Although never to return again, Dumbarton castle continued to be an essential piece in the complex mosaic that was Mary’s life.

Mary Queen of Scots biography

Lady Antonia Fraser’s weighty biography of Mary Queen of Scots goes into some detail about what she calls, “the boisterous spirits of her [Mary’s] noble.s”

Among the seemingly endless political intrigue in the Scottish court, Fraser examines a plot (1562), involving Bothwell and Arran, to have Mary abducted and moved to Dumbarton Castle.

In what was a convoluted scheme, it ended with Arran’s father, the Duke of Chatelherault, surrendering the command of the mighty Clyde Rock citadel.

In 1571, control was wrenched, in a daring escapade, from the governor Lord Fleming one of Mary’s most ardent supporters.

The raid carried out by one Captain Thomas Crawford of Jordanhill. One historian described it as the, “most eminent period in the castle’s history.”

Dumbarton Castle: Cromwellian Occupation

Of course, no story of Scotland is complete without mentioning Oliver Cromwell and true to form the Lord Protector played his part in the castle’s story.

Following the Scottish defeat at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650, Cromwell effectively controlled Scotland.

Dumbarton Castle in much the same way as other fortresses surrendered without a fight.

Accounts of Cromwellian occupation or to be more accurate of Cromwell’s second-in-command Major-General John Lambert paint an interesting picture.

There was no strengthening of the defences in preparation for Scottish reprisals; instead, the castle was stripped of many of its armaments.

Despite this, it remained in English hands and it seems that relations between the townsfolk and the military were cordial.

Today’s visitors to this historic Scottish castle, who have the energy to climb its seemingly endless flights of stairs which wind their way up to the Rock’s twin peaks, the Beak and White Tower Crag will find no visible signs of Dark Age Alcluith.

Despite this, enough documented evidence exists from a number of sources that allows a wonderfully evocative story to emerge of this ancient citadel, which in its many guises, has the longest recorded history of any British fortification.

Dumbarton Castle visitor information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the official castle website.