Linlithgow Palace, a key historical landmark in West Lothian, Scotland, is famously known as the birthplace of Mary, Queen of Scots (Mary Stewart), born in 1542 to Mary of Guise.

What was once one of Scotland’s grandest royal residences, now a Historic Environment Scotland property (HES) and Outlander filming location, lies around 20 miles from Edinburgh.

Today you can still explore within its ancient walls and walk through what remains of the Great Hall, bedchambers and royal reception rooms.

It’s not difficult to picture the kings and queens who also once passed this way. They were a who’s who of the people that shaped Scotland’s history.

highlights of Linlithgow Palace

Mary of Guise, wife of James V and mother of Mary, Queen of Scots, called Linlithgow Palace a “very fair place as fine as any chateau in France.”

Today although mostly ruined it is such an evocative place and well worth the short journey from Edinburgh.

- In 1424, James I began work on a new building after a fire that severely damaged the earlier residence.

- Mary. Queen of Scots was born in LInlithgow Palace in 1542. Her father James V was also born there in 1512.

- By 1583, parts of the building were in a ruinous state

- The Great Hall was built for James I.

- A magnificent courtyard fountain was added by James V in 1538.

- In 1745, Bonnie Prince Charlie stayed – the courtyard fountain ran red with wine to celebrate his visit.

- Linlithgow Palace was an Outlander filming location.

History of Linlithgow Palace

Historical records show that in 1143, during the reign of David I, the canons of Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh were granted skins from the cattle and sheep that grazed at the house (some sources have called it a castle).

That house became Linlithgow Palace. By that time a church and small town were also beginning to grow.

Archaeologists researching a much earlier period uncovered a few pieces of Roman pottery and a bell dating from the first century. It

That find allows us a tantalising glimpse of a long-forgotten occupation of the land.

At the end of the 13th century, Scotland once again prepared for battle with its more powerful southern neighbour after they discovered the Scots in secret negotiations with France.

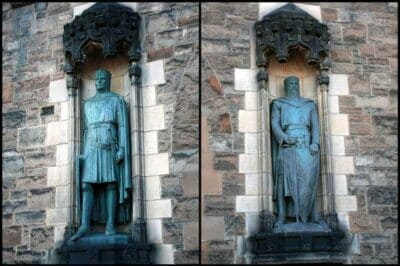

William Wallace and Robert the Bruce

By 1296, the two countries were at war and the long years of the Wars of Independence had begun giving the Scots two of their greatest heroes, William Wallace and Robert the Bruce.

Within a few years, England’s King Edward I (the Hammer of the Scots) arrived at Linlithgow and immediately saw the strategic advantage of strengthening the building.

Edward entrusted the work to one of Europe’s most experienced architects.

He was Master James of St George, already with an impressive record of building some of the great castles of Wales: Conwy, Harlech and Caernarfon.

Initially designed in stone, the plans were later modified, perhaps because of the cost and built almost entirely of timber.

Throughout 1302-03, masons, carpenters and scores of labourers toiled on this mammoth project.

Linlithgow Peel

In order to isolate the residence and church from the town, a ditch was dug across the promontory.

Behind that, they constructed a ‘pele’, a stockade of tree trunks (from the Old French pel meaning stake). A similar structure was also constructed on the side facing the loch.

The name Linlithgow Peel now applies to the whole of the royal park surrounding the Palace.

The work was finally completed at the end of 1303, making it an important supply base for the assault on Stirling Castle in 1304.

It remained in English hands for the next ten years. However, in the end, the garrison fell to Robert the Bruce after his great victory at Bannockburn.

Bruce’s biographer, John Barbour in his book The Bruce gave a poetic account of Linlithgow Peel

“And at Lythkow was then a pele..”

John Barbour

In 1425, a great fire swept through Linlithgow destroying much of the town leaving reigning monarch James I (1406-37) with a monumental task in order to rebuild it.

Undaunted he set about the work with gusto allocating over £5000 to build a ‘Pleasure Palace’ which would leave his subjects “gazing open-mouthed in admiration.”

No o conclusive documentation remains to tell us about the building work.

However, it’s thought James was responsible for the East Range and its Great Hall along with the kitchens and royal residences.

By 1429, the words peel and castle disappeared and were replaced with the palace.

His murder in Perth in 1437 brought building work to a halt. Bookkeepers estimated that he had spent over £7000, a huge sum that represented around a tenth of the king’s income.

He was succeeded by his young son James II (1437-60) who had little interest in continuing his father’s work.

In 1461, an unexpected guest arrived. It became a temporary refuge for fugitive English king Henry VI.

The new monarch’s passion was his arsenal of guns and canons, many of them housed in the royal palace before being deployed to James’s various military campaigns.

James II was killed at the Siege of Roxburgh Castle

It may not come as a surprise to hear that he was killed during a siege of Roxburgh Castle by an exploding cannon.

James III (1460-88) continued his grandfather’s work but it was only during the reign of his son that the pleasure palace envisaged by James I was almost completed.

James IV

His successor, James IV gave Scotland, for the first time in over a century, an effective king who could rule for himself.

The great theologian Erasmus spoke well of him.

“He had wonderful powers of mind, an astonishing knowledge of everything, an unconquerable magnanimity and the most abundant generosity.”

Erasmus

He spoke Latin (at that time the international language), French, German, Flemish, Italian, Spanish and some Gaelic, and actively pursued his interest in literature, science and the law.

With his patronage, the printing press came to Scotland. In addition the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh, St Leonard’s College, St Andrews and King’s College, Aberdeen were founded.

James commissioned building work not only at Linlithgow but also at Edinburgh and Stirling Castles

He developed a strong navy led by his flagship, the Great Michael, said to be the largest vessel of the time in Europe.

The accounts produced by the Lord High Treasurer in 1503 showed that his work at Linlithgow was largely finished. Just in time for his marriage to Margaret, daughter of English Tudor king Henry VII.

James gave the newly completed building to her as a wedding gift.

Flodden Field

Sadly the lasting memory of such an outstanding king will be his death at the slaughter of Flodden Field.

Up to 10,000 Scots were killed in this pointless battle along with their king, an archbishop, two bishops, 11 earls, 15 lords and 300 knights. In effect a whole generation of the Scottish nobility.

At the top of the north west turnpike stair At Linlithgow Palace is “Queen Margaret’s Bower” a lonely watchtower for a woman waiting for a husband who never returned.

“His own Queen Margaret, who in Lithgow’s home

Sir Walter Scott (Marmion)

All lonely sat, and wept the weary hour.”

James V born at Linlithgow Palace

More renovations, in the continental style, were done by James V 1513-42).

The windows in the Great Hall were re-glazed along with a new wooden ceiling in the chapel, extensive repainting throughout the building and a grand new fountain in the courtyard.

His French wife Queen Mary of Guise declared it a “very fair place as fine as any chateau in France.”

However much of the credit for this work should go to Sir James Hamilton of Finnart appointed Keeper of the Palace and Park and subsequently became the king’s Master of Works.

The Battle of Solway Moss

James, like most of his forefathers, was often at war with his southern neighbours and in 1542 his army under the leadership of his favourite Oliver Sinclair was routed at Solway Moss.

It was a devastating blow to the Scot’s king and in a state of some mental anguish, he went first to Edinburgh, then to the Hallyards, the Fife home of Sir William Kirkcaldy.

In a conversation with Kirkcaldy’s wife he told her he would be dead in 15 days. “On Yule day, you will be masterless and the realm without a king.”

Leaving Hallyards he went briefly to Linlithgow to see his wife Mary who was in the final stages of labour and then to Falkland Palace where he seemed to suffer a complete mental collapse.

When a messenger arrived from Linlithgow to tell him he had a daughter he said simply, “Adieu, fare well, it came with a lass, it will pass with a lass.”

The king was referring to the marriage of Marjory Bruce and Walter Stewart which had founded the Stewart royal dynasty.

Six days later, at the age of 30, he died. James’s prediction was right in one sense; the Stewart dynasty did end with a lass but not until the death of Queen Anne in 1714.

Mary, Queen of Scots

His lass was Mary Stewart (Mary, Queen of Scots) who spent the first seven months of her life in the royal nursery at Linlithgow before being sent to the relative safety of Stirling Castle. She later spent part of her life at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh.

It was twenty years before she returned. If life and the politics of the time had been kinder to Mary perhaps she would have spent more time in a place that her mother loved.

James VI

Her son (James VI, (1566 –1625) would also spend little time at the Palace particularly after the Union of the Crowns in 1603 when the Scottish royal court moved to London.

By 1583, parts of the building were in a perilous state and prompted a report from King James’s master of works Robert Drummond that the west range was “altogidder lyk to fall down.”

However, it wasn’t until 1607 that the inevitable happened.

The palace keeper reported that “This sext of September, betwixt thre and four in the morning, the north quarter of your Majesties Palace of Linlythgw is fallen, rufe and all…”

James finally returned to the place of his birth in 1617 and gave instructions that the North Range be rebuilt.

Linlithgow Palace: Charles I

Over the next two centuries, the Palace played host to a number of visitors.

Charles I (1625-49 ) arrived at Linlithgow in 1633 after a small fortune was spent on preparations for his visit.

In the town, the authorities cleared the middens and beggars from the streets and the magistrates bought themselves new robes.

Within two decades, the rise of Oliver Cromwell changed the political map of England and Scotland beyond recognition.

Charles had been defeated in the first of the English Civil Wars (1642-45) but remained defiant provoking a second civil war (1648-49.

His actions ultimately led to his execution in London on 30 January 1649.

The Battle of Dunbar

After an overwhelming victory over the Scots at Dunbar Cromwell stayed in relative comfort while his men camped on the peel while his cavalry and their horses were quartered in nearby St Michaels Church.

Little further work was done at Linlithgow and was described in 1668 as formerly “werie magnificent” but now for the most part ruinous.”

However, In 1724 Daniel Defoe described Linlithgow in glowing terms.

“The noble palace of the kings of Scotland, where they kept their court in great magnificence.”

Daniel Defoe

Bonnie Prince Charlie

Prince Charles Edward Stewart was the last of a long line of Stewarts to stay. When he arrived on September 15 1745, the ornate fountain in the courtyard ran with red wine in his honour. His visit however was brief and he left with an English army not far behind him.

That army, led by the Duke of Cumberland was in Linlithgow by January of 1746 and around ten thousand redcoats camped in the town and parts of the north range, resting overnight before pursuing the Jacobites north to the Highlands.

It was only a few short months later that the Prince was defeated at Culloden, the last battle ever fought on British soil.

But Cumberland’s soldiers had been careless and a fire took hold and the building was soon engulfed in flames.

Since that day Linlithgow Palace has remained uninhabited.

Today as you explore within its ancient walls, walking through what remains of the Great Hall, bedchambers and royal reception rooms it’s not difficult to picture the kings and queens who once passed this way.

They were a who’s who of the people that shaped Scotland’s history.

It’s perhaps fitting to leave the last word to Robert Burns who said when visiting in 1787, it’s “a fine but melancholy ruin.”

Related Content on Truly Edinburgh

Curious about learning more about Edinburgh’s historic sites? Check out these related articles.

Linlithgow Palace, birthplace of Mary, Queen of Scots: Visitor Information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the Palace website.