The Trossachs, in Gaelic means ‘bristling or rough area’. It’s an area that is today part of the Trossachs and Loch Lomond National Park.

The Trossachs is a region crisscrossed by ancient paths where Iron Age settlers eked out a living.

Romans made camp and drove roads, now long abandoned, brought Highland cattle to the great tryst at Crieff.

The Trossachs: part of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park.

Ben Venue and Ben A’an, home to some of the largest seawater lochs in Scotland, dominate this beautiful part of the world.

Its moorland, thick forests, meandering rivers and small towns and villages lie close to the Highland Boundary Fault.

The fault draws a geological line between Lowland and Highland Scotland.

Augustinian Inchmahome Priory

The region is home to the Augustinian Inchmahome Priory in the Lake of Menteith, a favourite haunt of King Robert the Bruce and refuge to the young Mary Queen of Scots after the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh.

It was the place where Rob Roy MacGregor went about his business.

While all add to the region’s rich historical legacy it is the Jacobean thread that for over half a century weaved its divisive way through communities, driving them apart or binding them together, hostages to shifting allegiances.

For many, it is this short chapter, which saw clan against clan as supporters of the Stuart royal dynasty, faced the proponents of Calvinist zeal, a defining episode in the region’s history.

Although It’s difficult to be exact about the borders of the Trossachs today, using the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park boundaries as a guide allows an exploration of an area that extends north from the east side of Loch Lomond to the ancient lands of Breadalbane, a natural partnership, where the Clan Campbell once dominated.

In 1874 Robert Louis Stevenson wrote, with more than a touch of irony, an essay On the Enjoyment of Unpleasant Places.

He said, “I suppose that the Trossachs would hardly be the Trossachs for most tourists if a man of admirable romantic instincts had not peopled it with harmonious figures and brought them thither with minds rightly prepared for impression…”

That man of admirable romantic instincts was Sir Walter Scott.

Following the publication of his poem Lady of the Lake and novel Rob Roy, which told of the region’s most famous son, the Trossachs became an increasingly popular destination for those seduced by Scott’s portrayal of the region.

It was the beginning of the tourist industry, as we understand it today.

A real sense of history pervades the area and while it isn’t possible to peer into every nook and cranny there are signs of a bygone era in the most unexpected places.

The Trossachs: Dunmore Hill Fort

An examination of the region’s earliest recorded days might take a person to the Pictish remains at Dunmore Hill Fort, close to the small town of Callander.

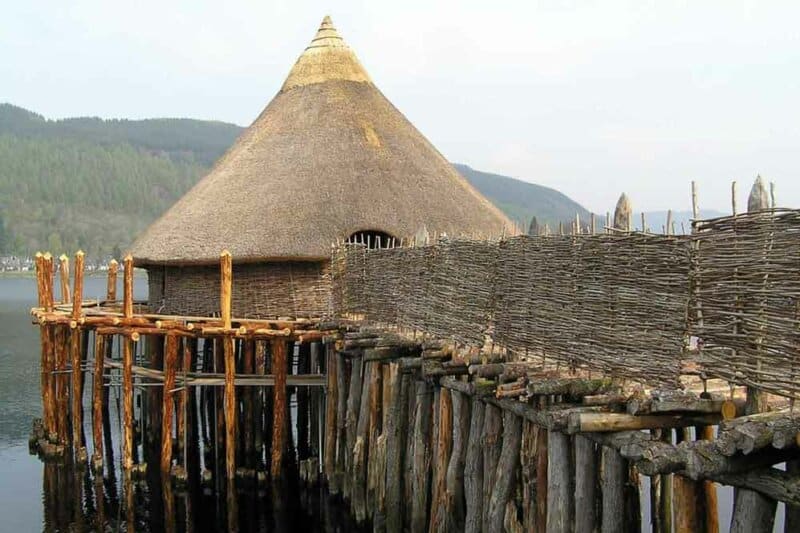

Or it might take them to the dark waters of Loch Tay at Kenmore where underwater archaeology has allowed a tantalizing glimpse into the lives of Iron Age crannog dwellers who chose this beautiful place to live and work.

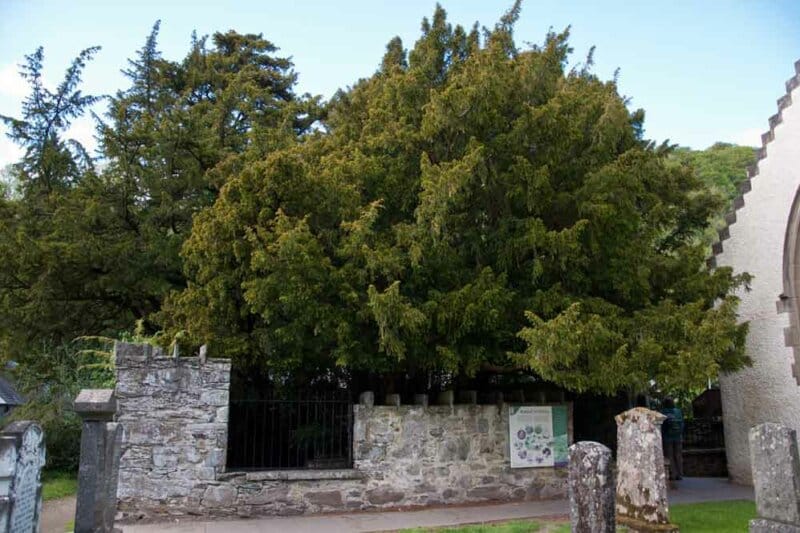

Close to Kenmore and the vast baronial pile that is Taymouth Castle is the small pretty village of Fortingall, the site of a celebrated yew tree thought to be the oldest in Europe.

Although experts cannot agree on the tree’s exact age could be as old as 5000 years, perhaps a witness to the lives of the region’s Iron Age settlers.

To the casual observer, it may seem that Fortingall played only a passing role in the region’s development and while the yew tree provides an interesting arboreal morsel, there is a much more unlikely historical reference that although almost certainly untrue has remained a point of discussion to this day.

Roman governor Pontius Pilate

Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland first published in 1577 was a work, said to have provided Shakespeare with an outline for that Scottish play.

It was also linked to the legend that Roman governor Pontius Pilate, the man who sanctioned the crucifixion of Jesus, was born at Fortingall.

Although the National Library of Scotland is quick to point out that Holinshed’s work contains no such mention of Pontius Pilate or Fortingall, the myth endures and adds an extra touch of notoriety to this sleepy part of the world.

Even such a remote location as Fortingall was not immune to the rising tide of Jacobite support that swept parts of Scotland in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

A valuable source of information relating to the Jacobite uprising comes from the pen of Duncan Campbell in the shape of Reminiscences and Reflections of an Octogenarian Highlander (Glenlyon History Society, 1910).

Campbell wrote, “In 1715 the men of the parish of Fortingall, gentry and commons, rose spontaneously on behalf of the Stuart dynasty. They thought it disgraceful that a ‘wee German laddie’ [Elector of Hanover, King George I] should succeed Queen Anne in the place of her brother.”

If Duncan Campbell’s words were not enough, a keen student of the period mind might uncover, in the records of a committee of the Diocese and Presbytery of Dunkeld, a report, which paints a vivid picture of Jacobite support at the heart of the community.

The church committee was appointed to report on the “conduct of the intruders into churches and parishes in connection with that Rising [Jacobite]”

It stated that “Mr Alexander Robertsone incumbent at Fortingall prays for the Pretender under the name King James the 8th; read or caused to be read all the Proclamations emitted by the Earl of Mar… and that he did read from his pulpit several traitorous and scandalous papers and intimations emitted by the rebels…”

Such conduct in the reign of George I was a serious matter.

Glenlyon, Scotland’s longest glen

Fortingall lies on the periphery of Glenlyon, Scotland’s longest glen, squeezed between Loch Tay and Breadalbane to the south and the wild moors surrounding Loch Rannoch to the north.

Tucked away in this lonely Trossachs glen are the ruins of Carbane Castle built during the 16th century by one Red Duncan Campbell the Hospitable, one of the early Campbell chieftains of Glenlyon, who it seems never quite lived up to his name.

Further along the glen is Meggernie Castle although now a private residence it began life as a tower house built by Mad Colin Campbell of Glenlyon towards the end of the 16th century. This particular Campbell did live up to his epithet.

Early records, for example, told the story of the Leachd nan Abrach, the rock of the Lochaber men where three dozen of them were hanged by Mad Colin for stealing livestock from the glen.

Glencoe Massacre

It is however his great-grandson Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon, the man responsible for leading the treacherous attack on the MacDonalds of Glencoe in 1692 who grabs the headlines.

While there is no doubting the complicity of Robert Campbell, the ‘massacre of Glencoe remains one of the most complex episodes in Scottish history and the roles of King William III and Sir John Dalrymple, Secretary of State for Scotland cannot be ignored.

A return to Fortingall’s parish records and Duncan Campbell’s research brings mention of Sheriffmuir.

This bleak and inhospitable moor, located only a few miles north of Stirling, was the site of the Battle of Sheriffmuir, the final fling in the first Jacobite uprising of 1715.

Earl of Mar led Jacobite forces at the Battle of Sheriffmuir

Sheriffmuir, the only major battle of the campaign saw the Jacobite forces, led by John Erskine the Earl of Mar, face a government army led by John Campbell, the Duke of Argyll.

Mar a man known for his frequent change of sides, hence his nickname of ‘bobbing John’, was formally a Commissioner during the Union negotiations, Secretary of State for Scotland but crucially a man with inadequate military experience.

Also at Sheriffmuir – Rob Roy MacGregor

John Campbell, Duke of Argyll, the leader of government forces, who fought under Marlborough during the War of the Spanish Succession, was the opposite, a man with a considerable military pedigree.

Despite this, the battle was inconclusive although the Jacobites might claim victory on strategic grounds. Among the clan chiefs who played their part at Sheriffmuir was Rob Roy MacGregor.

Those with more than a passing interest in the life of Rob Roy face a number of difficulties for in the words of writer and historian Nigel Tranter his life was, “surrounded by a mass of semi-legendary tales” with a comparatively small amount of accurate primary material available for research.

To some, he was a folk hero, a Scottish Robin Hood who took from the rich and gave to the poor but others took a different view.

Bruce Lenman, Professor of Modern History at St Andrews University and author of The Jacobite Risings in Britain takes a more considered view.

He described Rob Roy as, “a former speculator in livestock who had failed in business and had turned to selling a rough and ready sort of insurance known as blackmail.”

Sir Walter Scott

In Sir Walter Scott’s words, “The character of Rob Roy is, of course, a mixed one.

His sagacity, boldness, and prudence, qualities so highly necessary to success in war, became in some degree vices from the manner in which they were employed…”

Tranter, while acknowledging that Scott’s hugely successful work was largely responsible for spreading the fame of Rob Roy takes issue with some of the content including the analysis of Rob Roy’s role at Sheriffmuir where he is accused by some of, “standing idle.”

Tranter is quick to argue that much of this Highland cateran’s story, as written by Scott in 1818, relies heavily on anecdotal evidence collected in the MacGregor lands almost 100 years after his death.

Robert Roy (Ruadh or Red) MacGregor was born into a Jacobite family in Glengyle at the head of Loch Katrine in March 1671 a difficult time in Scotland.

It was a period that Bruce Lenman examined in some detail. He said, “It is the Restoration era, and especially the reign of Charles II from 1660 to 1685, that the intellectual roots of post-1688 Jacobitism must be sought.”

By 1689 Robert MacGregor and his father Colonel Donald MacGregor of Glengyle had survived the Battle of Killiecrankie a bloody Jacobite response to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the installation of Protestant monarchs William and Mary.

Battle of Killiecranke

Following Killiecranke, Rob Roy was forced to take his mother’s name of Campbell, when his own proud MacGregor name was outlawed because of his family’s part in the Jacobite ‘conspiracy’. I

It wasn’t an easy choice considering the enmity between Campbells and MacGregors.

In the early part of 1693, he married his cousin Mary of Comar and turned from politics to cattle and with the patronage of the Duke of Montrose became successful, gaining the lands and title of the Laird of Craigroysten and Inversnaid as a result.

By 1712 his life turned sour when after borrowing a large sum of money from Montrose his head drover stole it and fled.

Despite MacGregor’s promise to repay the money, Montrose branded him a thief and declared him an outlaw, burning his house and evicting his family.

In turn, Rob Roy made open war with the duke and under the guardianship of the Earl of Breadalbane, the local chief of clan Campbell and deadly rival of Montrose, began a different life.

He rustled cattle and extorted money in return for ‘protection’ twice being jailed but escaping on both occasions.

Finally, in 1727 he was arrested and sentenced to transportation but subsequently pardoned. He died at Balquidder in 1734.

Cattle tryst at Crieff

The growth of the cattle tryst at Crieff, a familiar town to Rob Roy, was rapid as increasing numbers of drovers brought their cattle to be sold there.

From Argyll, they came through Glen Dochart and Loch Earn, from Skye and the outer islands the ancient drove roads snaked across the wild country of Rannoch Moor to Loch Tay and Loch Earn.

Reports for October 1723 said that 30,000 beasts were traded with many being taken to England by the same drovers who brought them from the Highlands.

The one shilling a day earned for the trip was a welcome addition to any profits made at the market.

Drove Roads of Scotland

A.R.B. Haldane in his Drove Roads of Scotland, one of the great classics of Scotland’s history spoke in some depth about the Crieff trysts.

One particularly enlightening comment from Haldane summed up the relationship between drover and town.

He said, “The writer of the new Statistical Account of the Parish of Monzie describing the past glories of Crieff tryst reported that when the market was at its height the inhabitants of the surrounding country went in fear of their lives from the Highland drovers who broke into their houses…”

A number of commentators likened it to the Wild West.

Rob Roy now lies at peace, together with his wife and two of his sons, in the quiet churchyard at Balquidder,.

His headstone carved with the words, added after his death, “MacGregor despite them” which says much about the man’s spirit.

Today an inquiring mind will take note of Red Robert’s proud but fading epitaph, and appreciate its significance, or stop to consider a castle ruin or Jacobite relic and understand their role in people’s lives.

Perhaps now considered mundane by some, part of the well-worn tourist trail envisaged by Sir Walter Scott but not so, for they are a small reminder of a defining moment in Scotland’s history.

More Scottish history articles

Trossachs Visitor Information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the national park website.