1451: Founding and early history of the University of Glasgow

William Turnbull founded the University of Glasgow in 1451, bringing his vision of higher education to Scotland. Inspired by the University of Bologna, the oldest institution of learning in the western world.

Turnbull laid the groundwork for what would become one of the nation’s leading centres of education and intellectual excellence.

He was a man with an impressive pedigree – a man with royal connections.

Turnbull had an MA degree from the University of St Andrews and was a student of canon law at the University of Louvain in Belgium.

He was an adviser and royal secretary to James II and keeper of the Privy Seal from 1400 to 1448.

Most importantly he was also Bishop of Glasgow from 1448 until his death in 1454.

Historian John Durkan attests to the close relationship between Turnbull and the king when he says, “The king showered Glasgow with favours.”

It was Turnbull who convinced King James to ask the Pope to establish a university in Glasgow. Sadly, his original petition has been lost.

However, many scholars believe that the request was inspired by Turnbull’s desire to increase his personal status in the community and his desire to give the See of Glasgow the same standing as that of St Andrews.

Woodman confirms this by saying, “The bishop-founders no doubt revelled in the personal prestige that erecting institutes of higher learning bestowed on them.”

Clearly Turnbull’s academic and ecclesiastical work didn’t curtail his involvement in the murky world of Scottish politics.

One incident later documented by John Law, a canon of St Andrews, said that Turnbull was implicated in the murder of William Douglas, 8th Earl of Douglas in February 1452.

University of Glasgow: historical timeline key dates

1451: the University of Glasgow was founded by a papal bull issued by Pope Nicholas V, making it the fourth-oldest university in the English-speaking world.

1560: following the Scottish Reformation, the university shifted its focus to Protestant theology and education, aligning with the new religious landscape.

1637: the university received a significant endowment from Charles I, which helped stabilize its finances and expand its academic offerings.

1870: the university relocated from its original High Street location to its current home at Gilmourhill in the West End of Glasgow.

1892: women were officially admitted to the university for the first time, marking a significant step toward gender equality in education.

1957: the university became the first in Scotland to have an electronic computer, demonstrating its commitment to technological advancement.

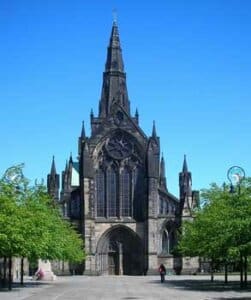

First lectures held in Glasgow Cathedral

In the early years of the university, lectures were held in Glasgow Cathedral’s lower church and the nearby Dominican priory.

Indeed, throughout the first hundred years of its existence, the university enjoyed a close relationship with the cathedral and played an important part in church reform.

At first only undergraduate arts degrees were obtainable at Glasgow. Teaching was carried out by regents who took their students through the entire period of study in all subjects.

The Bachelor of Arts degree required three years of study. The Master of Arts was awarded after five years of study in Greek, Latin, moral philosophy, natural philosophy, physics and/or mathematics.

Only students in the Master of Arts programme were deemed official members of the university with the right to vote in the election of the chancellor.

A letter from Mary Queen of Scots

Following the Reformation of 1560, the university was in terrible condition. Most of the catholic staff were forced to flee, student numbers decreased and many of the buildings were in a dilapidated state.

A letter written by Mary Queen of Scots to the university reveals her shock at the “half built” schools and buildings.

What’s more the university chancellor Archbishop James Beaton, a confidant and supporter of Mary had also left for the safety of France.

He took with him some of the valuables belonging to Glasgow Cathedral and the university including the precious Bull from Pope Nicholas V and the mace, a symbol of the university’s academic authority.

While the mace was returned some years later, the Papal Bull was never seen again. Despite its loss, it remains the authority by which the university awards its degrees.

Andrew Melville, a Scottish scholar, theologian and religious reformer who studied at the University of St Andrews was a towering figure in Glasgow’s development.

After a number of years spent on the continent, he returned to Scotland in the summer of 1574 and encouraged by Archbishop Boyd, the university’s chancellor, he accepted the post of Principal of the University of Glasgow.

Melville revitalised teaching methods, scrapping the outdated system of regenting and replacing it with specialist teaching.

The curriculum was streamlined, with the introduction of Ramist logic, rhetoric, geometry and arithmetic.

In addition, new instruction in Greek, Aramaic, Syriac and Hebrew reflected his humanist training and European experience. His list of ‘approved authors’ included Plato, Aristotle and Cicero.

Melville had been one of the figures of the Reformation and was the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.

New charter granted by James VI

Melville also oversaw the issuance of a much-needed new charter, the Nova Erectio granted by James VI in 1577.

While there is no doubting the impressive nature of his work, which should never be undervalued, the analysis clearly shows the importance of the state, church and local officials contributed to the rise in the university’s fortunes.

“God’s sillie vassal.”

Despite the essential help of the king, Melville remained hostile to royal involvement, on one occasion unwisely describing the king as, God’s sillie vassal.”

In 1606 he was imprisoned in the Tower of London for five years and then banned from returning to Scotland after his release. He died in France in 1622.

In 1631, work began on new university buildings on the High Street close to Glasgow Cathedral. Construction continued slowly, as money allowed.

By the beginning of the 18th century, student numbers increased to around 400 and within 30 years, seven professorships were either created or restored.

Law became a recognised faculty with its own chair and botany, zoology and chemistry became part of the faculty of medicine.

The University of Glasgow and the Scottish Enlightenment

The latter half of the 18th century witnessed the growth of extraordinary intellectual activity known as the Scottish Enlightenment, a period that transformed not only Scotland but also had a profound impact on the wider world.

While Edinburgh’s prominence often leads to the assumption that it was the epicenter of this intellectual revolution, such a view overlooks the crucial contributions of Glasgow and Aberdeen.

Indeed, some contemporary historians continue to argue that a compelling case can be made for Glasgow as a pivotal birthplace of this remarkable era.

The University of Glasgow, in particular, served as a fertile ground for the innovative thinking that defined the Enlightenment.

The opening salvo from Glasgow might well have been the publication of Francis Hutcheson’s Inquiry into the Ideas of Beauty and Virtue in 1724.

Hutcheson, an Ulsterman, was the chair of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow from 1730 to 1746. He introduced lectures in English rather than Latin.

His substantial influence spread far beyond the confines of Scottish academia with his work being taught thousands of miles away at American universities.

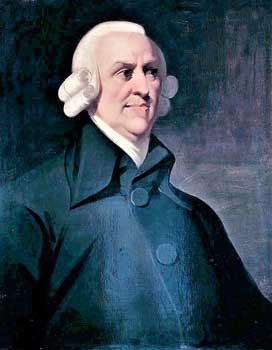

Occupying the chair of moral philosophy after Hutcheson were other pillars of the Enlightenment. Thomas Cragie in 1743 and then Adam Smith the distinguished historian, philosopher and political economist.

Today, Smith’s contribution to the university is widely remembered thanks to a building, library, chair and research foundation named in his honour.

Notable alumni of the University of Glasgow

Throughout the history of the University of Glasgow, many notable graduates have made significant contributions in various fields.

Here are a few examples of alumni who have had a lasting impact, from scientists and philosophers to writers and lawyers.

- James Dalrymple, 1st Viscount of Stair (1619–1695): Studied law at the University of Glasgow, later becoming a prominent lawyer and judge, known as the “Father of Scots Law”.

- James Watt (1736–1819): Attended the University of Glasgow as a mathematical instrument maker, where he developed his interest in engineering and mechanics.

- David Livingstone (1813–1873): Studied medicine and theology at the University of Glasgow, preparing for his career as a missionary and explorer.

- John Buchan (1875–1940): Studied classics at the University of Glasgow, where he developed his literary skills before transferring to Oxford.

- William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (1824–1907): Studied mathematics and natural philosophy at the University of Glasgow, later becoming a professor and contributing significantly to thermodynamics.

- Thomas Campbell (1777–1844): Studied law at the University of Glasgow. He was a celebrated poet and author, known for works like The Pleasures of Hope and his advocacy for education reform.

- Thomas Reid (1710–1796), a philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment, founded the Scottish School of Common Sense and emphasised the reliability of human perception. He succeeded Adam Smith as the Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow and was a joint founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

As distinguished as they all were, they were only a few of the many thousands who earned their places in this grand old ‘stadium generale’.

Pioneering Women at the University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow’s commitment to expanding access to education took a significant step forward in 1892, when women were first admitted.

This marked a turning point, leading to the emergence of remarkable female graduates who broke barriers and made lasting contributions to their respective fields.

The examples below are only two of many notable female alumni of the university of Glasgow:

In 1894. Marion Gilchrist was the first woman to graduate from the University of Glasgow and the first woman to gain a medical degree in Scotland.

In 1895, Isabella Blacklock was the university’s first female arts graduate and in 1919 Madge Anderson, a Glasgow girl, became the first woman to earn a law degree as well as the first woman to be admitted to the bar in Britain.

The University of Glasgow expansion

Towards the end of the 19th century, the High Street buildings proved inadequate, prompting the university to relocate west to Gilmourhill, which remains its primary campus today.

Expansion at Gilmourhill continues, establishing the University of Glasgow as a global leader in higher education, with a vibrant community of approximately 43,000 students from over 140 countries.

Conclusion: the University of Glasgow has grown from its founding in 1451 to become a major global university. In the process it has become a key part of Scotland’s educational story, alongside other Scottish universities.

Today, Glasgow continues to educate students from around the world.

- More information: visit the official University of Glasgow website for more information.