While the history of the University of St Andrews dates to 1413, the town it took its name from is much older.

The Annals of Tigernach, written in Ireland in AD 747, documented the first hard evidence of a permanent settlement on the site now known as St Andrews.

By the early 10th century, it was an important religious and royal centre.

The town was raised to Burgh status by Bishop Robert and confirmed by King David I at some point between 1144 and 1153.

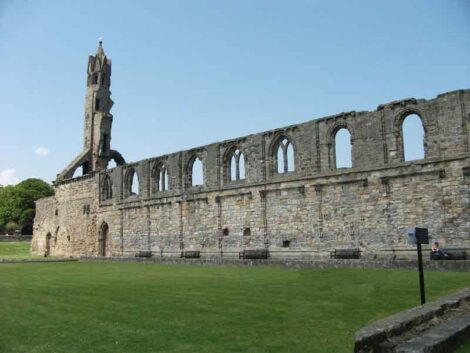

Building on its magnificent Cathedral probably began around 1160, it was finally dedicated, in the presence of Robert the Bruce, in 1318.

Although its geographical position was in some ways a barrier to population growth, St Andrews, as the seat of the most powerful bishopric in the country was the obvious choice for Scotland’s first university.

The University of St Andrews became the third oldest in the English-speaking world after Oxford and Cambridge.

Scotland’s first university

Traditionally Scots had travelled to Oxford, Cambridge, Paris and other European cities for their higher education. Two particular events changed this:

- Scottish students were forced to abandon the two great English universities during the Wars of Independence.

- As the division in the Catholic Church deepened during the Great Schism, Boniface IX and Benedict XIII, two rival popes, took different paths.

With the French clergy supporting Boniface and the Scots following Benedict, the formerly close ties with the University of Paris were lost.

The story of the foundation of the University of St Andrews should properly begin with Henry Wardlaw, nephew of the powerful Cardinal Walter Wardlaw, Bishop of Glasgow.

Wardlaw was an educated man, taking a BA at the University of Paris and studying Civil Law at Orléans and Avignon before becoming a Doctor of Canon Law.

He was appointed Bishop of St Andrews in 1403.

Chronicler Walter Bower a contemporary of Wardlaw, and one of a community of Augustinian canons, who served at St Andrews Cathedral, described him as a gentle man.

Despite this he reproached him for his famously lavish entertainment which saw him spend beyond his means.

In February 1412, Wardlaw issued an Episcopal charter of foundation assigning privileges to a small existing academic group established in 1410 by Scottish masters returning from Paris.

Papal Bulls & the foundation of the University of St Andrews

The need to seek Papal authority for the confirmation of the charter saw a petition in the name of James I, at that point still a prisoner in England, dispatched to Benedict.

At that time, the Pope was safely settled in the impressive Knights Templar-built Pensicola Castle (Castillo Del Papa Luna) on Spain’s Costa del Azahar.

It was duly ratified by a pontiff, already known as a patron of art and learning and no doubt also grateful for Scottish support, in a series of six Bulls, dated August 28, 1413.

J. Maitland Anderson writing in the Scottish Historical Review in 1911 suggests that “This plurality of bulls issued by the same Pope and bearing the same date, at the founding of a university, is probably without parallel in the academical history of Europe.”

In the first and principal Bull, the Pope summarised the reasons for the foundation of a university at St Andrews.

He said, “There were many risks and dangers by land and sea to which Scottish clerks were exposed in quest of instruction in the Faculties of Theology, Law, Medicine and the Liberal Arts: the battles they had to fight, the detentions they had to endure, the broils they had to encounter…on their way to the Universities of other countries…

“…considering also the peace and quietness which flourish in the said city of St Andrews and its neighbourhood, its abundant supply of victuals, the number of hospices and other conveniences for students, which it is known to possess, we are led to hope that this city, which the divine bounty has enriched with so many, may become the fountain of science…”

The Papal Bull arrives in St Andrews

The mission to carry the Papal edict from Spain to Scotland was entrusted to Henry Ogilvie, a priest of the Diocese of St Andrews.

The precious documents didn’t reach the town until February 3, 1414.

They came, said Bower, “on the Morrow of the Purification of Our Lady, which happened to be a Saturday. As soon as Ogilvie’s arrival was known, the sounds of bells went forth from all of the churches of the town.

On the following day, a solemn assembly of the whole clergy was held, and the remainder of the day was passed amid scenes of great hilarity…”

The University’s foundation would have conferred added dignity to the town while bringing further personal prestige to Wardlaw, no doubt motivated to raise the profile of his diocese above others. Indeed, the initial focus was to improve the clergy’s education.

Historian Isla Woodman argued that aside from prestige his charter was more concerned with endowing the University with trade privileges and tax exemptions, which extended to all staff, academic and non-academic.

Wardlaw envisaged the, “flourishing of university and city together, the power of the university rendering the city powerful.”

Henry Wardlaw’s charter

Neither Wardlaw’s charter nor the papal bulls made any provisions to house the new university, a situation which prompted Woodman to argue that the “infant institution was little more than a concept – a community of scholars lacking proper monetary endowment as well as a physical base.”

She continued by saying the lack of buildings, “offered the dual advantage of keeping the pursuit of learning at the front of members’ minds while allowing mobility in the times of plague.”

It was 1419, before it received any kind of endowment. The first one recorded came from Robert of Montrose,the Prior of St Andrews who donated the Chapel of St John on South Street, close to the cathedral.

This building became the College of St John’s for “theologians and artists.” In 1430 Wardlaw added adjacent buildings to house a teaching faculty for the Arts known as the Pedagogy.

Sadly, there are no surviving records from either. St Mary’s College founded by Archbishop James Beaton in 1539 now stands on this site and today houses the University’s School of Divinity.

In many ways, Beaton’s motivation for founding the college was similar to Wardlaw’s – the better education of parish priests.

Although papal authority was received in February 1538, it was a further year before the official foundation was recognised.

On a contemporary note, during a period of Cathedral renovation, the head of Wardlaw’s effigy was discovered hidden in a wall and the torso was found used as a window lintel.

In 2013, a newly commissioned statue was unveiled in the grounds of St Mary’s College.

The first rector and Dean of the Faculty of Arts was Lawrence Lindores who, like Wardlaw, was educated at the University of Paris taking his MA in 1393, and later teaching in arts until c. 1401.

It wasn’t until May 1408, that he was recorded in Scotland where he was styled rector of Criech and the Papal Inquisitor of Heretical Pravity in Scotland.

Despite his pivotal university role, he is best remembered for rooting out heretics.

Two trials ended in burning, one in Perth in 1408, and the second in St Andrews involved Paval Kravar, better known in Scotland as Paul Craw.

Craw was a native of Bohemia and a follower of John Wyclif, a critic of the established church.

He was accused in the summer of 1433 of spreading heretical ideas. Bower said Paul Kravar, “confessed that he was sent from Bohemia by Prague heretics to imbue the Scottish kingdom with the evils.”

In memory of Paul Kravar

Interestingly, as recently as September 2016, a plaque was unveiled in the town, by the Ambassador of the Czech Republic in memory of Kravar.

Lindores had considerable academic success with his commentaries on Aristotle being widely read in mainland Europe,

His work was known to influence Nicholas Copernicus the father of modern astronomy and developing his understanding of physics.

The arts curriculum was composed almost exclusively of Aristotle’s logic, physics, natural philosophy and metaphysics after a foundation of elementary logic.

To obtain a degree students had to study and copy out the required texts.

James I, finally released after 18 years of captivity, returned to Scotland in 1424.

The following year, anxious to make his mark, he made ambitious plans to develop Perth in a similar way to Oxford.

As part of that vision, he attempted unsuccessfully to move the university from St Andrews to Perth.

Among the other colleges, St Salvator’s, the college of the Holy Saviour, is the oldest. It was founded in 1450 by Bishop James Kennedy, the nephew of James I and second chancellor of the university, as a college of Arts and Theology.

There are no visible signs of this building today. In its place is the United College of St Salvator and St Leonard.

What does remain, although much changed, is the beautiful St Salvator’s Chapel. Described as the “hub of life in Scotland’s oldest University,”

St Salvator’s Chapel, part of Bishop Kennedy’s college, serves both as a college chapel and a collegiate church open to the wider community.

The chapel suffered badly during the Reformation and if a reminder of these tumultuous times is needed the initials “PH” carved in the cobbles underneath the bell tower do just that.

In 1528, at a nearby spot, Patrick Hamilton was burned at the stake for his Protestant faith. He was the first martyr in the Scottish Reformation.

St Andrews Cathedral

The cathedral and castle both met similar fates. Of the many great medieval institutions only the university persisted.

At the centre of the Reformation was John Knox, a student at St Andrews, probably matriculating in 1529.

Among his teachers was John Mair distinguished historian, philosopher and theologian, a man with considerable influence.

Knox in his History of the Reformation said that Mair was a man, “whose word was then held as an oracle on matters of religion.“

It’s an interesting statement from Knox considering in his commentary on Aristotle, Mair declared, “In all opinions he [Mair]agrees with the Catholic and truest Christian faith in all its integrity.”

Andrew Melville was a towering post-Reformation figure often seen as the successor to John Knox.

Following his excellent work at the University of Glasgow, he held the post of Principal of St Mary’s College from 1580 to 1607 and for the period between 1590 and 1597 was rector of the university.

As an educator, churchman and politician he was often a thorn in the side of James VI and I, in his attempts to exercise a royal and Episcopal authority over the Scottish kirk.

That he spent time in the Tower of London should come as no surprise to those who know his story.

For keen students of the period the works of James Kirk and Stephen J Reid, who drew from previously unpublished material held at St Andrews and the National Library of Scotland, are essential reading.

Over the following centuries, the University slowly evolved, although academic endeavour was often punctuated by incidents, some violent, some peaceful and some that were just surprising.

In 1470, a number of students and several masters were expelled for attacking the Dean with bows and arrows.

Rather bizarrely in 1544, in the middle of the Rough Wooing crisis, the University said no to beards, gambling, football and the carrying of weapons.

In 1645-1646, the Scottish Parliament, driven out of Edinburgh by the plague, took up residence in the University’s Public School, now known as Parliament Hall.

First graduate from the University of St Andrews

During the 19th century, the pace of change quickened with new developments in teaching and research.

It was 1895 when the first female student, Agnes Forbes Blackadder, graduated 482 years after William Yellowlock, (1413) the first ever graduate.

One man with strong links to the University was Andrew Carnegie, a Dunfermline man, one of the world’s greatest industrialists and most generous philanthropists.

Carnegie was Rector of Scotland’s pioneering stadium generale from 1901 until 1907.

At his installation, he said, “I am hereafter one more St Andrews man who will proclaim the indefinable charm under whose potent spell I now stand before you.”

Through the centuries many other great men and women have been attracted to the town.

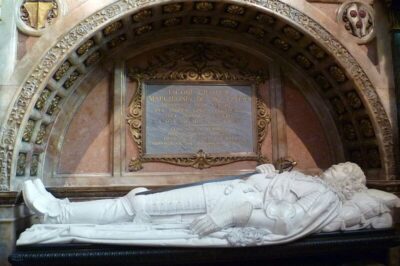

Memorial to Marquis of Montrose at St Giles’ Cathedral

While the University’s Alumni are an essential part of its history there are inevitably too many to mention.

However, given a license to cherry pick there are a number who have left an indelible mark on Scotland’s development.

James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose, who initially fought for the Covenanters during the English Civil Wars before switching to the Royalist side and his greatest enemy Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquis of Argyll were both educated at St Andrews.

Others of note include Adam Ferguson, philosopher and historian of the Scottish Enlightenment, philosopher John Stuart Mill, author Rudyard Kipling and John Napier the inventor of logarithms.

From a contemporary perspective, it’s impossible not to mention the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge who studied and met at the university.

There is a strong connection between the university and the United States.

James Wilson who helped draft the American constitution and signed the American Declaration of Independence studied Divinity and Classics.

John Witherspoon was awarded a Doctorate of Divinity and Benjamin Franklin received an Honorary Doctorate of Laws.

Today the University of St Andrews is a world-class centre of learning.

It’s dynamic and forward-thinking but still remains, quite correctly, conscious of its unique history and heritage – still relevant in a modern world.