John Knox House is one of Edinburgh’s oldest visitor attractions, a reminder of the prominent Scottish Reformation leader.

Although much of it was constructed in the mid-16th century, there are still remnants dating to the 1470s.

It’s a house that tells the story of the Scottish Reformation of 1560, a tumultuous time in Scotland’s history.

The first record of a house on the current site dates to December 1525.

At that point, Christina Reidpeth or Arres, having inherited the property from her father Walter Reidpath, passed the property to her son John Arres.

Further records of 1556 show the owners of the house as Mariot Arres and James Mossman. This is where the story gets really interesting.

A panel on the outside of the first floor shows the initials of the couple carved on an armorial panel with Mossman’s arms.

‘M A’ represents Mariot Arres but Mossman’s initials show not as ‘J M’ but ‘I M’.

A new façade was added in 1559. Part of the design was a sundial, “showing Moses receiving the light of God symbolised by the sun on Mount Sinai. An inscription reads, ”Luve God abuve al and yi nychtbour as yi self.”

Supporter of Mary, Queen of Scots

James Mossman, a wealthy goldsmith, was a staunch Catholic and an ardent supporter of Queen Regent Mary of Guise and her daughter Mary Queen of Scots.

When she finally returned from France to Scotland in 1561, she appointed Mossman, as a reward for his support, as goldsmith and jeweller to the crown, and master of the Royal Mint.

In the wake of the Scottish Reformation and the ensuing exile of Mary Queen of Scots (deposed in 1567 in favour of her infant son James VI) Edinburgh descended into chaos.

James Mossman was caught up in the turmoil and lost not only his positions at court but his life too.

Supporters of the Protestant James VI and supporters who wanted to see the return of Catholic Mary faced each other in civil conflict.

James Mossman became part of an armed political group that wanted the queen’s return. Known as Castilians in Edinburgh they took control of Edinburgh Castle between 1571 and 1573. What followed was the ‘Lang Siege’ of Edinburgh Castle.

In what is a complicated yet compelling story, James Mossman, following the surrender of the queen’s men was arrested, charged with treason and taken from the castle to Holyrood.

From there he made his final journey to the Mercat Cross where he was hanged.

Did John Knox ever live in John Knox House?

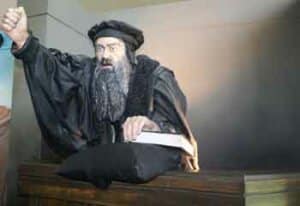

Knox, a key figure in the Scottish Reformation and one of the founding fathers of the Church of Scotland was also the first minister of St Giles’ Cathedral after the Reformation.

But he ever live in the house we know today as John Knox House? The answer to that is hotly debated.

Tradition dictates that the firebrand preacher lived in the house for a few months before his death in November 1572. However, there is no real evidence to support that.

While acknowledging the debate between some of Scotland’s best-known 19th century historians, the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) refers to a report by historian Dr Marguerite Wood.

The report says that the connection of the building with Knox rests on a tradition that only goes back to 1784.

It was, it seems, the year that the Hon. Mrs Murray, on a visit to Edinburgh, wrote in her subsequent book published in 1799 of a “tottering bow window to a house, whence Knox thundered his addresses to the people.”

What to see at John Knox House

Today John Knox House is part of the Scottish Storytelling Centre which operates from an adjacent building. They do however share an entrance.

Much of the ground floor is taken up with the bookshop. From the gallery, you can see sections of the original luckenbooths, essentially little medieval shops which were rented to merchants to sell their merchandise. Among them would have been tailors, furriers and cutlery makers.

- The Book Room has a collection of texts from the Reformation period, including ones from Calvin, Erasmus and Knox. There is a copy of George Buchanan’s History of Scotland and the treasured Bassendyne Bible, the first English Bible to be printed in Scotland.

- The Mossman Room displays, among other things, the tools of the goldsmith’s craft.

- The Pew Room is dedicated to the works of John Knox.

- The Oak Room a favourite meeting place among important members of Mary Queen of Scot’s court has an elaborately painted ceiling with fairies, devils and signs of the zodiac. It dates to around 1600.

- The adjoining gallery to the Oak Room, traditionally considered to have been Knox’s study, contains a copy of his last prayer which begins, “and so I end, Rendering my troubled and sorrowful spirit in the hands of Eternal God…”

In 1849, the Dean of Guild Court decreed that the house’s ruinous state was an “encumbrance to the street.”

However, whether the house was or was not occupied by John Knox, it is almost certainly the case that his name saved the building from demolition.

Following a spirited campaign by a number of organisations including the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland a demolition order was avoided and John Knox House opened as a museum in 1853.

A word on the Scottish Storytelling Centre

The Scottish Storytelling Centre, of which John Knox House is a part, is a lively arts venue with a regular programme of storytelling, theatre, music and much more.

The centre, formerly known as the Netherbow Arts Centre opened in 2006. It was the first purpose-built storytelling centre in the world, cementing Edinburgh’s place as a UNESCO City of Literature.

Read more about the Storytelling Centre programme.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH & READING

- Miller, R., 1899, November. Where did John Knox Live in Edinburgh? And the Legend of’John Knox’s House.’. In Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Vol. 33, pp. 80-115).

- Wilson, D., 1891, November. John Knox’s House, Netherbow, Edinburgh. In Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Vol. 25, pp. 154-162).

- Guthrie, L.C.J.G., 1898. John Knox and John Knox’s House. Oliphant, Anderson, and Ferrier.

- Hulbert, E.B., 1899. John Knox and John Knox’s House.

- Heisch, C.E., 1881. JOHN KNOX AND HIS TIMES. Golden hours: a monthly magazine for family and general reading, 14, pp.752-758.

John Knox House – visitor information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the official John Knox House website.