The history of Dunbar reveals that David II created it a Royal Burgh in 1370. This small East Lothian town lies around 30 miles from Edinburgh.

Dunbar, in Gaelic, means the fort of the height and is attributed by English chronicler Raphael Holinshed to the events of the Battle of Scoon (Scone) c. 835-9.

During the battle, Kenneth I, ably assisted by one of his army captains called Bar, defeated Drusken, King of the Picts.

In reward, Kenneth presented the castle to Bar, hence the name Dunbar – Dun (fort) and Bar. Other etymological definitions have Bar (Barr) as meaning summit.

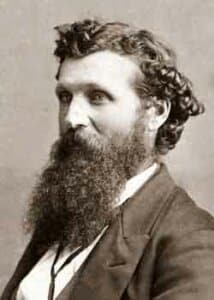

The history of Dunbar: John Muir

Dunbar is uniquely associated with John Muir, born in the town on 21 April 1838 but like many Scots of the time, John aged only 11 and his family made the crossing to the United States in search for a better life.

As a writer, naturalist, conservationist and founder of the national parks system in the United States, John Muir is perhaps better known in his adopted country.

However, his links with his birthplace remain strong, celebrated in an excellent museum and interpretive centre dedicated to his life and work.

Craggy ruins of old Dunbar Castle

Although Muir made his name on the other side of the world, it’s clear where his inspiration came from.

He said, “When I was a boy in Scotland, I was fond of everything that was wild… I loved to wander in the fields to hear the birds sing and along the shore to gaze and wonder at the shells and seaweeds, eels and crabs in the pools when the tide was low; and best of all to watch the waves in awful storms thundering on the black headlands and craggy ruins of old Dunbar Castle.”

In 1843, a time when John Muir was not yet five years old, writer, historian and Victorian social commentator `Thomas Carlyle came to Dunbar, and casting his inquisitive eye over the town he described it as the

“…fort on the point, high and windy, looking down on its herring boats, over its grim old castle, now much honeycombed, on one of these projecting rock promontories with which that shore is niched and vandyked, as far as the eye can reach…”

Thomas Carlyle

Carlyle’s casual observation of the town’s herring boats is a reminder that those ‘silver darlings’ were an important catch for fishermen who followed their migratory trail along Britain’s east coast.

By early August, of the 19th century, the fleet was based in Dunbar for about six weeks; it was a big event.

In 1858 the Chief Boatman at Dunbar Coastguard said, “Having occasion to count the boats attending the fishing off Dunbar, I have frequently counted from seven to eight hundred.”

Earlier records show that in 1656 Oliver Cromwell referred Dunbar’s herring fishing. He noted that the fish was cured and barreled up, either for merchandise or sale to the country people who come thither far and near at the season…”

Although few physical remains of that, “grim old castle” now exist to remind us of that period when it took centre stage, surviving records, however brief, allow a thought-provoking glimpse into a much earlier world.

Unsurprisingly however documents relating to early Scottish history are rare and some may be regarded as apocryphal but there are some intriguing snippets of information available. They tell us a little but leave us looking for more.

Declaration of Arbroath

They tell us for example that St Wilfrid Bishop of York was imprisoned in the castle, c 678 by Ecgfrith King of Northumbria, that in 858, Kenneth II burned the castle and later a Dunbar was one of the Scottish peers to attach their seal to the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320.

The first person to take the name Dunbar was Gospatric (servant of St Patrick), Earl of Northumbria (Bernicia) who after the Norman invasion of England in 1066 fled north to the safety of the Scottish court.

With him came the Saxon heir Edgar Atheling and his sister Margaret, later wife to King Malcolm III (Canmore).

Gospatric’s future service to the Scottish king saw him granted the castle at Dunbar, which he turned from wooden construction to one of stone.

With the castle came the lands adjacent to it. It was the start of a dynastic process that saw his descendants amass vast estates and take the title ‘Earl of Dunbar and later the Earl of March.

This small east-coast town was the site of the first battle of the Scottish Wars of Independence.

Ditchburn and MacDonald, Medieval Scotland 1100-1560 said, “The Anglo-Scottish conflict that began in 1296 had its roots in dynastic accident,” a reference to the death of King Alexander III in 1286 and the subsequent death of his only heir Margaret, an infant of the Norwegian court.

Thomas the Rhymer

As a brief side note to the death of Alexander, some chroniclers relate the story of Thomas the Rhymer (True Thomas of Ercildoun), a Borders laird with the gift of prophecy.

Thomas arrived at Dunbar Castle the day preceding the death of Alexander to be asked if anything of note would happen the next day.

The Rhymer predicted that it would bring, “The sorest wind and tempest that was ever heard of in Scotland.”

Scotland was now without a ruler and unable to decide who should take the throne, so the help of Edward I of England was sought.

Eventually, John Balliol was selected from a list of 13 claimants which included Patrick Dunbar (Blackbeard) the 8th Earl of Dunbar the first to also carry the title Earl of March.

It’s worth noting at this point that the use, by previous writers, of the titles Dunbar and March and their numbering is sometimes contradictory and therefore confusing.

For example, some writers style the above (Blackbeard) as the 8th Earl of Dunbar, and 1st Earl of March others have him as 8th Earl of Dunbar and March.

Where there are conflicting views on whether the incumbent was known as Dunbar or March this writer has used what he regards as the most authoritative sources for his research.

John Balliol’s reign (1292-6) was bedevilled by Edward’s insistence on overlordship a condition he had reluctantly agreed to.

It was however not to last and John to frustrate Edward joined with the French in the Auld Alliance a strategic partnership designed to restrain English expansion.

The unwelcome union infuriated Edward as did Balliol’s attack on Carlisle Castle

The inevitable result was war and Edward’s army under John de Warrenne, 6th Earl of Surrey, a veteran of Edward’s Welsh campaigns, was dispatched to ‘deal’ with the Scots.

Following the sacking of Berwick, it moved on to Dunbar.

The subsequent Battle of Dunbar, fought a few miles to the south-west of the castle ended with a decisive English victory.

A number of the surviving Scottish nobles fled to the castle for safety but were later handed to the English by castle governor Richard Sirward.

The Scotchronicon

This event was later recorded in the Scotchronicon, the Chronicle of Walter Bower, written about 145 years after the event.

Bower wrote, “Richard Siward by name handed them all, to the number of seventy knights, besides the Earl of Ross and the Earl of Monteith, to the King of England, like sheep offered for slaughter.

Without pity, he handed them over to suffer immediately various kinds of death and hardship.”

However, because of Bower’s reputation for historical inaccuracy a full picture of the events of Dunbar, 1296 remains a matter of debate.

Interestingly in a paper written by Education Scotland, the writer considers the value of Bower’s contribution.

He makes the point that there is no mention of the commoners in the Scottish army, at least 10,000 of them, mainly untrained farmers.

It also fails to mention that a simple manoeuvre by the Earl of Surrey was interpreted as an English retreat prompting a fatal charge by the Scots.

Nor does it record that the death or capture of Scottish nobles led to a dangerous power vacuum exacerbated when John Balliol was later captured and forced to surrender his kingdom to Edward.

Bruce’s victory at Bannockburn

Following Robert Bruce’s victory at Bannockburn in 1314, Edward II fled from the battlefield to the relative safety of Dunbar Castle where he received help from Patrick the 9thEarl to escape by sea to England.

Despite this support for the English cause, it was also a time for prudence and Patrick sought peace with Scotland’s king.

However, after the Scot’s defeat at the battle of Halidon Hill in 1333, the Earl once again swore allegiance to the English crown (Edward III).

In the long and often bloody history of Dunbar Castle, one particular incident stands out.

It involved the Countess of Dunbar, forever remembered as Black Agnes because of her dark hair and swarthy complexion.

She was born in 1312, the daughter of Robert the Bruce’s nephew, Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray and married to the fickle 9th Earl whose loyalty swayed in the prevailing political winds of the time.

By 1337, following a period of English occupation, the castle was once again restored to Patrick who departed on military duties to the north of Scotland leaving only his wife Agnes and a handful of men.

It seemed too good an opportunity to miss and Edward III, like his father and grandfather before him wanted the strategically important castle returned to English hands.

More Scottish History articles

In the second week of January 1338, with Berwick already taken, William Montague, 1st Earl of Salisbury arrived at Dunbar to lay siege to the castle.

For five months, despite the large numbers of soldiers and the mighty siege engines facing her, the Countess of Dunbar kept the English at bay.

Now firmly established as a Scottish folk hero, the story of her bravery and determination to see off the enemy is better remembered today than all the sieges and bloody battles that took place at Dunbar.

“That brawling, boisterous Scottish wench” is a fitting epithet that some attribute to Salisbury as he admitted defeat, packed up and headed home.

The site of Dunbar Castle was strategically important for whichever side had control. It was an ideal landing place on the coast beyond Berwick particularly when that town became part of England in 1483

In recognition of that value and to deny English occupation, an Act of the Scottish Parliament was passed in 1488 directing that the Castle of Dunbar was destroyed. It instructed that the castle be, “Cassyne doune and alutterly distroyit…”

Regardless of parliament’s wishes, Sir Walter Scott argued that this, “Ordinance was carried out till nearly a century afterwards.”

The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) while acknowledging the 1488 parliament’s instructions noted that James IV constructed a castle at Dunbar.

“Apparently completed in 1501.” RCAHMS also records, “In the next reign Dunbar Castle was possessed by John Duke of Albany, Governor of Scotland during the minority of James V.”

history of Dunbar: Mary Queen of Scots

The fortress has a strong connection with Mary Queen of Scots and her mother Mary of Guise who as Regent of Scotland made major improvements to the building allowing the garrisoning of a number of French troops who remained until 1561.

It was the younger Mary in a period of heightened religious and political tension who, heavily pregnant with the future King James VI, took refuge at the castle in April 1566 after the savage murder of David Rizzio at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh.

Mary was once again at Dunbar the following year after the murder of her second husband Lord Darnley, held against her will at the castle by James Hepburn, the Earl of Bothwell who subsequently became her third husband.

Within months it was Bothwell who was forced to flee to Dunbar following defeat at the battle of Carberry Hill in June 1567 by an army led by the Lords of the Congregation, a group of Scottish Protestant nobles supported by Elizabeth I of England.

While Bothwell escaped to Dunbar Castle and eventually to exile, Mary, a Catholic, was taken by her Protestant captors and imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle.

Following Mary’s abdication in July 1567, the Scottish Parliament ordered the destruction of Dunbar Castle.

Battle of Dunbar

In September 1650, a Scottish army of 22,000 men under the command of General David Leslie was soundly defeated by a Cromwellian force, of half the size, at the Battle of Dunbar.

Leslie was hampered in no small way by Scots Covenanting ministers who purged the army of 3,000 experienced officers because they were not, “theologically sound.”

Cromwell’s victory allowed him to push on and take Edinburgh, the start of the process which saw Scotland incorporated into the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1653

For centuries Dunbar was a town with a family and their castle at its heart. Both played their part in the sometimes labyrinthine world that was Scotland’s political and spiritual evolution.

Today visitors, with more peaceful intent, flock to the town’s beautiful beaches and challenging links golf courses.

They remember the contribution made by John Muir and while there is no public entrance to what remains of the castle they must surely stop and wonder at the stories it could tell.

VISIT SCOTLAND – DUNBAR VISITOR INFORMATION

For further information and help planning your visit to Dunbar, go to the Visit Scotland website.