Early Glasgow History

This article covers some of the people, places, and events that shaped Glasgow’s early history.

That early history reveals activity in the area long before St Kentigern (St Mungo) arrived.

Like many historical events, the first stirrings of Glasgow, like any new city are perhaps a little foggy.

Glaswegians grow up learning of the story of St Kentigern, or St Mungo as he is better known, who came to the area in the 7th century.

He built his first wooden church on the site of the present Glasgow Cathedral.

This almost certainly meant that there was already a gathering of people living within the immediate area.

Govan Stones

The Govan Stones, dating from the 9th to 11th centuries, were originally part of a significant early Christian site in Govan, Glasgow.

This collection of 31 carved stones includes remarkable pieces like the sarcophagus and hogback stones, which are examples of early medieval artistry.

These carvings offer a valuable glimpse into the spiritual and cultural life of the time, with influences from both Christianity and Viking traditions.

The stones are celebrated for their intricate craftsmanship, reflecting the skill of early medieval sculptors.

They also highlight Govan’s historical connections with Norse culture, as the site was likely influenced by Viking settlers during this period.

Today, the Govan Stones are housed in the Govan Old Parish Church in Glasgow, where visitors can view the collection through exhibits and guided tours.

“Remarkably, every single one of these Viking-age treasures has lain in Govan Old churchyard for over 1000 years.”

Govan Heritage Trust

- The University of Glasgow Govan Old Archaeology Portal has more information about the Govan Stones.

Bishop Jocelin created a burgh at Glasgow

Early Glasgow history records the consecration of Bishop John Achaius to the See of Glasgow in 1114.

We also know that by 1175, a charter granted by William the Lion gave Bishop John’s successor Bishop Jocelin the right to create a burgh at Glasgow.

Other documents from the 13th century give us the first mention of a bridge over the River Clyde, and what that meant to the people.

It was the fast-flowing waters of the Molendinar Burn and not the Clyde that turned the town mills.

The sandy-bottomed Clyde at low tide was very shallow, in some places only a foot deep. Records tell us it was sometimes liable to ruinous flooding.

However, for medieval Glaswegians its river was an important source of water and fish, particularly salmon.

It would be hundreds of years before it was dredged allowing cargo and passenger boats to dock in the heart of the city.

By the early 14th century, there is evidence of a growing population and an expansion in a number of directions.

However, the ecclesiastical heart still dominated the city both in terms of the structure of power and its geographical position, which looked down on the embryonic development below.

Glasgow Cross

Glasgow’s growth continued throughout the following century, new homes and businesses appeared on a main street, which led to Glasgow Cross.

From the Cross small roads wandered, almost in a haphazard manner towards the river.

Part of this ancient thoroughfare was called the Briggait, gait or gate being the old Scots word for a walk or way.

The Gallowgate, a familiar name to all Glaswegians wandered east over the Molendinar burn to St Thenaw’s Gate.

However, despite its expansion, Glasgow’s west coast location meant it remained in terms of political or strategic importance a minor player, with Edinburgh and Stirling the dominant towns.

University of Glasgow: part of the early history of Glasgow

In 1451 the University of Glasgow was founded after King James II of Scotland asked Pope Nicholas V to grant a Bull authorising Bishop William Turnbull to set up a university.

It is the second oldest in Scotland, (fourth in the English speaking world), a younger brother to St Andrews University founded in 1413.

The university’s charter states that Scotland’s latest seat of learning should be modeled on the University of Bologna in Italy and should have a faculty of Arts, which all students must attend before progressing to the faculties of Divinity, Law or Medicine.

Classes were originally held within the cathedral before moving to a house in nearby Rottenrow, which became known as the pedagogium or ‘Auld Pedagogy’.

It then moved to the High Street before its final move in the 19th century to its present home in the West End of the city.

By 1455 Andrew Muirhead was consecrated Bishop of Glasgow, a post he retained for 18 years. He was a sophisticated and well-travelled man, educated in St Andrews and Paris and we know he was also a visitor to Rome.

Provand’s Lordship

During his tenure as Bishop, he was responsible for some of the early development of the university and some of the city’s finest Medieval buildings including the Hospital of St Nicholas.

Glasgow: Provand’s Lordship

The Provand’s Lordship, which took its name from the estate of Provan on the east side of Glasgow and is the city’s oldest remaining building was built by Muirhead around 1471, as part of the Hospital.

It was used as a manse for the canons from nearby Glasgow Cathedral and although much reconstruction and renovation have been done it still stands today.

If you look carefully you can see Bishop Muirhead’s coat of arms, three acorns, carved into one of the gable ends.

The Church gave the holder of this prebend (a portion of the property of the cathedral) granted to a prebentary for his maintenance) wide-ranging power and the canon became known as the Lord of Provan.

Provan Hall, which dates from the 16th century, the country house of the old prebend of Provan is also still in existence, although it now languishes within the rather austere post-war housing estate of Garthamlock.

Inside Provand’s Lordship

The house originally had nine self-contained rooms each with a fireplace and two windows that looked east towards city’s most prominent house of worship.

Although not large or particularly grand by today’s standards the rooms offered the resident cleric a fair degree of comfort.

The Bishop of Glasgow’s palace was a fortified structure. Archaeological evidence shows that it started life as an unpretentious stone tower surrounded by a protective moat. The building gradually evolved as successive bishops took their seats.

Glasgow becomes an Archbishopric

The rising power of the city became more apparent when Bishop Blacader convinced the Scottish King James IV that like St Andrews, Glasgow should become an archbishopric.

A brief history of St Andrews Castle(Opens in a new browser tab

On 9 January 1492 Pope Innocent VIII announced that Glasgow should receive this elevated status, with Blacader as the first archbishop.

With the post came the responsibility for a number of other dioceses: Dunkeld, Dunblane, Galloway and Argyll.

This new prominence brought increased power and wealth to the Cathedral and fresh building work on the bishop’s palace began, within forty years it had been transformed.

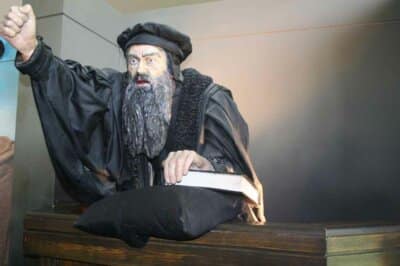

John Knox

The palace became a castle of impressive proportions, a fifteen feet high wall enclosed five circular towers and a gatehouse at the southeastern corner.

However, repeated attacks meant that “It became so badly battered that it no longer functioned as a fortress.”

The emergence of John Knox in 1560 brought cataclysmic change to Scotland as the old Catholic order was swept away.

The army of Protestant Lords, the Earls of Moray and Argyll overran the Cathedral, the bishop’s castle and the incumbent Archbishop Beaton was forced to flee to France.

By August of 1560, John Knox had demanded that all altars be cleansed of iconography and to “purge the kirks of all kind of monuments of idolatrye.” Consequently, many of the stained glass windows and paintings were destroyed.

Defeat of Mary Queen of Scots

Within a few years (1568) the defeat of the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots at the Battle of Langside, now part of Glasgow, saw her hopes of remaining in Scotland dashed, reinforcing the new Presbyterian order.

Display of medieval artefacts in Glasgow Cathedral

Andrew Melville, the Principal of Glasgow University had already demanded the magistrates pull down the Cathedral.

Now they had no choice but to obey and the call went out for labourers to start the demolition.

But the crafts guilds of the city were having none of it, their members had laboured long and hard to build it and they certainly were not going to allow Melville to pull it down.

They made it very clear that he would come to a sticky end if any attempt was made to demolish the building.

Leaving the upheavals of the Reformation behind it, Glasgow over the following centuries continued to grow.

Today the home of the shrine to St Kentigern is overlooked by the Glasgow Necropolis, a vast Victorian garden cemetery.

A View of the City of Glasgow

In 1736, a local Glasgow man John McUre published A View of the City of Glasgow, one of the first histories of the city,

“The city is surrounded with Corn-fields, Kitchen and Flower -gardens, and beautiful orchyards, abounding with Fruits of all Sorts, which by Reason of the large and open streets, send furth a pleasant and odiferous smell.”

John McUre

By the middle of the 19th century, Glasgow’s population had exploded. Thousands from Ireland and the Scottish Highlands poured into the city desperately looking for work.

Glasgow’s Slums

This huge influx of people created appalling slums, particularly around Glasgow Cross and the High Street. Poor sanitation brought disease and death from cholera, 4000 people died in an outbreak in 1842.

As the narrow streets and the squalid and rat infested tenements were finally swept away as part of Glasgow’s improvement plans with them went much of the city’s Medieval heritage.

Today a visitor to the city in search of the past must be grateful to the Provand’s Lordship Society formed in 1904 when plans to extend the nearby Royal Infirmary were proposed and it seemed likely that the house would be knocked down.

Many of Glasgow’s prominent citizens got involved in the campaign to save the historic building, which at that time was home to a number of businesses, a barber shop, greengrocer and a sweet shop.

In 1927, the help of shipping magnate and philanthropist Sir William Burrell was enlisted to help acquire furniture and other objects for the house in order to recreate the interior as it might have looked at the end of the 17th century.

Today the Provand’s Lordship is once again a reminder to visitors of the history of Scotland’s biggest city.

It’s an opportunity to reflect on the lives of the people who lived there and devoted their lives to their Christian cause.

Visitor Information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the Glasgow Cathedral website.