Early Parliaments of Scotland

Scotland’s earliest parliaments housed the ‘three estates’ of nobles, clergy and burgesses. We now have a clearer understanding of them thanks to the work of Brown, Roland, Tanner, et al.

They were distinguished academic contributors to The History of the Scottish Parliament (to 1707), part of the Scottish Parliament Project at the University of St Andrews.

The work, which boasts an impressive bibliography, was a gargantuan task. For those interested in such matters it’s certainly worthy of a more detailed investigation.

Sadly because of Edward I’s attempt to take advantage of Scotland’s succession crisis, details of the earliest parliamentary records are sketchy and open to debate.

What, if anything made them different from previous gatherings, particularly to the king’s great council (Curia Regis)?

Kirkliston colloquium held in 1235

Despite this knowledge gap it is possible to make some observations.

In England, the word colloquium, used during the reign of Henry III, seemed to be synonymous with the word parliament.

In Scotland, the earliest documented reference to the term points to the Kirkliston (near Edinburgh) colloquium held in 1235 during the reign of Alexander II.

Alison McQueen one of the contributors to the Scottish Parliament Project argues that the word parliament was not used to indicate a correlation between the monarchy and law or taxation.

Instead, she said, it was clearly associated with the unique circumstances surrounding the death of Alexander III in 1286, the absence of a recognised successor and the subsequent Guardianship of Scotland.

It was, said McQueen, a scenario that required assemblies or parliaments to advise on the way forward.

To re-enforce her argument McQueen cites the evidence that points to only one colloquium and one parliament held during the thirty-seven years of Alexander III’s reign in comparison with the seven parliaments that were held during the period February 1293-October 1295.

Scotland’s parliament only had a single chamber

Unlike England’s two-chamber (bicameral) parliament, a House of Commons and a House of Lords, Scotland had only a single chamber (unicameral), housing the ‘three estates’ of nobles, clergy and burgesses.

Although the expression ‘Tres Communitates’ was mentioned in 1357, the term the Three Estates was first recorded in 1373.

The matter of what language was spoken at early Parliaments raises some interesting discussion. It’s an issue that the Scots Language Centre investigated at some length.

We know that initially proceedings were recorded in Latin and from 1424; Acts of Parliament were scribed in Scots, a date that also marks the earliest legislation still in force. The Royal Mines Act which decreed that all gold and silver mines belong to the crown.

Certainly, from that date, if not earlier, the Scots tongue was competing strongly with Latin as the preferred language for politics.

It also continued to be the language of debate even after the Union of the Crowns in 1603 but as the 17th century progressed a substantial proportion of documents were Anglicised.

No records exist to tell us what language was used by speakers during the sessions.

However, the Scots Language Centre says it’s reasonable to argue that language mirrored the ethnic composition of the members.

Therefore French, particularly during the 12th and 13th centuries was probably used to some extent and for Parliaments held north of the River Forth it was likely that some Gaelic was spoken.

Over the early centuries assemblies met in a range of locations, occasionally outdoors but more commonly in royal palaces, abbeys and castles. Even parish churches or convents were chosen to house what tended to be fairly short affairs, sometimes lasting only a week.

Locations of early parliaments of Scotland

Among the early geographical locations selected were: Ayr and Glasgow in the west, Auldhearn in the north but mainly in sites clustered around the east coast and central belt. Edinburgh, St Andrews, Dundee, Arbroath and Perth were often used.

However, it wasn’t until the reign of James II that sessions held in royal or ecclesiastical buildings became less common and community venues were used more frequently.

Certainly from 1438 to 1560, barring war and disease, the Old Tolbooth, ‘the Heart of Midlothian’, in Edinburgh was the setting for many of the early parliaments of Scotland.

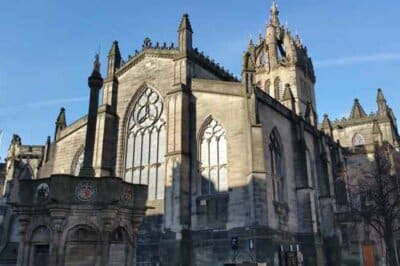

Robert Chambers, writing in, Traditions of Edinburgh published 1868, painted an evocative if unsavoury picture of the Tolbooth. “Where Mary [Queen of Scots] assembled her parliaments… it stood, elbow to elbow, as it were, with St Giles Church.

“Antique in form, gloomy and haggard in aspect, its black stanchioned windows opening through its dingy walls like the apertures of a hearse…”

The National Covenant

As the role of Parliament developed the peripatetic nature of its meetings became impractical and a permanent home was needed.

A purpose-built chamber was constructed, on the orders of Charles I, on the old burial grounds behind St Giles’ Cathedral.

It opened for business in 1639 only a year after the signing of the National Covenant a time when Covenanting principles demanded the dismantling of royal authority over Parliament.

Today that building, with extensive changes, houses Scotland’s Court of Session.

The Heart of Midlothian

To mark the original site of the Edinburgh Tolbooth, finally demolished in 1817, ‘the Heart of Midlothian’ a heart-shaped granite mosaic was set into the pavement close to St Giles Cathedral.

By 1645 the English Civil War was raging and plague had arrived in Edinburgh forcing the Estates to abandon their new home and seek healthier climates in other parts of Scotland.

They reconvened again in Edinburgh in 1646 but the capture of the city by Oliver Cromwell, following the Battle of Dunbar in 1650, meant that legislators were again forced out of the capital.

Subsequently, as Cromwell strengthened his grip on the country, Scottish affairs were run from Westminster.

It wasn’t until the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 that Scotland’s political masters met in Edinburgh again.

The last Parliament of an independent Scotland

The last Parliament of an independent Scotland sat in four sessions between 1703 and 1707.

It was a period punctuated by a bitter debate over the Scottish Act of Security 1703-4, a mechanism that allowed the Estates to appoint a different monarch to that of England.

The conditions attached to the Act were essentially a manifesto for independence, a return to the days before the Union of the Crowns in 1603 when both the Scottish monarchy and Parliament were independent of England.

The English were appalled at such a possibility that could have seen the restoration of a Jacobite monarch on the Scottish throne.

The implications for them were serious; the country was at war in Europe and a fully independent Scotland might renew their military alliance with the French, with disastrous results.

In retaliation, the Westminster government passed the Alien Act of 1705 which threatened to block Scottish exports to England, its main trading partner and remove Scottish rights to any property owned south of the border.

It declared that if commissioners were not appointed to negotiate for Union between Scotland and England and discussions were not advanced by Christmas Day 1705 severe penalties would be imposed.

It meant the important Scottish exports, to its southern neighbour, of coal, linen and cattle would be suspended.

When you consider that by 1700, with the decline of European trading links, almost half of Scotland’s commerce (by value) was with England it was obvious that the new legislation would cause further severe damage to an already fragile Scottish economy.

It was simple but effective economic blackmail.

Add to the equation the still prevalent conditions created by the widespread famine and the disastrous Darien expedition of the 1690s and It became clear that some kind of agreement had to be reached.

Sadly there was no consensus within Scotland’s political elite on what that should be.

In the same way as with any modern government wishing to push through legislation, the size of the ruling party majority and its ability to attract smaller groups was key.

In that final Parliament the Court Party under the Queen’s Commissioner, the Duke of Queensberry was in favour of the Union and had about 100 supporters out of a total of 227 members.

They had the responsibility of ensuring that plans for the Treaty of Union were accepted.

Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun

The Jacobites (Cavaliers) were bitterly opposed, and the Country Party, led by the Duke of Hamilton was a loose alliance, ‘notionally’, against the Union.

It drew support from fervent anti-unionists like Lord Belhaven and Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun. From the Country Party, an offshoot, the Squadrone Volante emerged and argued for some form of Union.

Historian TM Devine, The Scottish Nation 1700-2000, described the Court party as a “Formidable political management machine that contrasted with the disarray of the parliamentary opposition which failed to capitalize on the national resentment to union…”

The closing debate before the Union took place between 3 October 1706 and 16 January 1707.

It was a session in which Queensberry, backed by English money, handed out honours, pensions and other financial incentives to ‘persuade’ members to back the Treaty.

Members of the Squadrone Volante were, unsurprisingly, the biggest beneficiaries of Queensberry’s largesse.

Perhaps the largest inducement was a promise, contained in Article 14 of the Treaty, to pay the ‘Equivalent’, a sum of almost £400,000 designed to offset Scotland’s future liability for part of England’s national debt and as recompense to those who suffered financially in the Darien scheme.

Much of the money found its way into the pockets of the Squadrone Volante group which had supported Queensberry’s ruling party.

The Equivalent was, “Creative accounting of a high order of ingenuity,” said historian Paul Henderson Scott.

However, after an angry debate, it was agreed to send commissioners to London to draw up a treaty. Hamilton proposed that Scots commissioners be chosen by the queen and parliament agreed. It was a body blow to the anti-unionists.

Hamilton’s motives for the betrayal of the anti-union cause have been examined in some detail by Henderson Scott who poses the question,

“Why did Hamilton behave with such extraordinary vacillation or duplicity?”

Paul Henderson Scott

A number of possibilities are examined but according to Scott, the most likely was that his self-interests prevailed over his political instinct.

Quite simply, as an owner of estates in England, he had too much to lose. Whatever the reason Hamilton as the de facto leader of the opposition, “Effectively undermined and destroyed it.”

The Scottish commissioners, selected by the queen

The Scottish commissioners, selected by the queen, were mainly composed of Queensberry and his followers.

The Squadrone Volante was excluded apart from one notable exception, George Lockhart of Carnwarth, a Jacobite supporter of the Stuart royal dynasty and nephew to influential English commissioner Lord Wharton, a relationship which goes a long way to explaining his inclusion.

The Articles of Union, negotiated in just three days by thirty-one Scottish and thirty-one English commissioners, were finalised in London on 22 July 1706.

With agreement, the threat from the Scottish Act of Security and the English Alien Act receded.

Article 1 of the Treaty began “That the two kingdoms of Scotland and England shall upon the first day of May next ensuing the date hereof and forever after be United into one Kingdom by the name of Great Brittain…”

A further twenty-four articles followed and on the allotted date, 16 January 1707 the Treaty was ratified.

Related content

An angry mood swept the streets of Edinburgh and people made violent threats against the ‘treaters’.

John Erskine, the 6th Earl of Mar said, “The mob of this town are mad and against us,” while English propagandist Daniel Defoe said that he, “Found the wholl City in a Most Dreadful Uproar and the High Street Full of Rabble…”

Despite the Edinburgh mob and amidst continuing accusations of skulduggery, Scotland’s proud record as an independent nation ceased, as parliamentary business in Edinburgh was brought to an end, two months after the ratification of the Treaty, by Commissioner Queensberry.

Queensberry said, “The Publik Business of this Session being now at an end, it is full time to put an end to it.” It was said one observer, a melancholy session.

Today’s Scottish Parliament

In July 1999, the grand royal opening ceremony of Scotland’s newly devolved Parliament, in its temporary home, was a day when the country remembered its history, puffed out its chest and presented a new face to the world.

That special day when the country grabbed the limited powers on offer from Westminster marked the beginning of another chapter in the long and sometimes murky story of Scotland’s Parliaments, in all their many guises.

It was part of a process that had evolved since early kings and their councils made decisions on the essential matters of the day.

SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT: visitor information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the Parliament website.

references: research & data

- Paul Henderson Scott, Andrew Fletcher and the Treaty of Union, (Saltire Society, 1992) pp 24, 25, 31, 45, 46, 47, 57- 73, 210, 223.

- Paul Henderson Scot. Still in Bed with an Elephant, (Saltire Society. 1985) pp 39,45,49, 67.

See also: further reading

- University of St Andrews: The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707.

- UK Parliament: Act of Union 1707.

- The University of St Andrews: The political role of the Three Estates in Parliament and General Council in Scotland, 1424-1488.

- University of St Andrews: The Scottish Parliament: A Historical Introduction.