The story of Dunfermline Abbey began in the 11th century during the time of King Malcolm III, Queen Margaret and their youngest son who became King David

It’s the final resting place of Robert the Bruce (his heart was taken to Melrose Abbey).

The historic building sits in the bustling Fife town of Dunfermline – in Gaelic Dun Fearam Linn, the fort in the bend of the stream, around two miles north of the Firth of Forth only 18 miles from Scotland’s capital city.

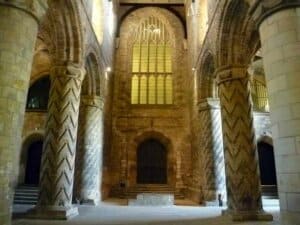

Visitors to Dunfermline will clearly see the division between old and new. The Norman style nave of the medieval monastic church built by David I forms the western end. Today’s parish church, built in the early 19th century, over the original medieval choir, forms the eastern end.

To the south, are the remains of the early monastery with the ruins of the Royal Palace nearby.

On top of the church tower, the name of “King Robert the Bruce” is carved in stone, a prominent reminder of his close association with the abbey.

King Malcolm III and Queen Margaret

Margaret, Anglo-Saxon princess and sister of Edgar the Atheling who had, with her mother, brother and sister, fled to Scotland following the arrival of William the Conqueror and his victory over Harold, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, at the Battle of Hastings.

Her subsequent marriage to Malcolm was almost certainly one of political convenience, although a much more ‘romantic’ version of the couple’s union exists. Despite this political expediency, it seems the royal couple got on better than might have been expected in the circumstances.

Close to the abbey, within Pittencrieff Park (known locally as the Glen), are the ruins of Malcolm’s Tower thought by some to be the original site of the marriage of Malcolm to Margaret.

Others suggest it was the birthplace of Matilda (Maude) their daughter and future wife of England’s Henry I.

However archaeological investigation shows the ruins dated to the late 13th or early 14th century and not the 11th century. Scottish academic Richard Oram suggests the tower was probably part of the abbey precinct, perhaps part of the defences built during the Wars of Independence.

John of Fordun

Scottish chronicler John of Fordun (died c. 1384) has left us an early and evocative description of Malcolm’s Tower. He said, “It was a place extremely strong by natural situation and fortified by steep rocks; in the middle of which is a pleasant level, likewise defended by rock and water.”

He tells us too that in 1070 the nuptials were, “magnificently celebrated at a place called Dunfermelyn which the king then held as his fortified residence.”

Margaret’s influence on Malcolm was substantial and after her death, her confessor Turgot, Prior of Durham and Bishop of St Andrews, wrote his Life of St. Margaret Queen of Scotland,

He said “First of all in regard to King Malcolm: by the help of God she made him most attentive to the works of justice, mercy, almsgiving and other virtues. From her he learnt how to keep the vigils of the night in constant prayer…”

St Margaret’s Chapel: Edinburgh Castle

These are fine words from Turgot, indeed much of what is known about Malcolm comes from this source but it should be remembered that Malcolm lived in a violent world with little peace in his kingdom.

He was often making war in England in an attempt to expand his territory and raise booty for the royal coffers and his own passage to the throne saw him kill Macbeth, a man whose name lives on thanks to the pen of William Shakespeare.

Given such a lifestyle it was perhaps inevitable that Malcolm’s own death came in battle at the siege of Alnwick Castle in Northumberland.

Malcolm III, 1058-1093 – Malcolm Canmore (Gaelic Ceann-mor, great head), unlike previous Scottish kings whose experience was shaped mainly in the Gaelic Highlands of Scotland, was brought up in the harsh Anglo-Scandinavian world of northern England.

In an interesting side note, Richard Oram makes the point that a number of scholars now believe the epithet Canmore applies not to Malcolm III but to King Malcolm IV.

Margaret, pious and learned brought the latest in reformed orders and learning from the Anglo-Norman world introducing great change to the Celtic church in Scotland.

Later canonized by Pope Innocent IV in 1251 she remains the only Scottish saint.

Thomas Owen Clancy and Barbara E Crawford, The Formation of the Scottish Kingdom, argued that the evidence clearly shows that Margaret was, “very much in touch with Norman standards of reformed cult and worship, requesting Archbishop Lanfranc to send a complement of Benedictine monks from Canterbury for the church dedicated to the Holy Trinity, which she and Malcolm founded…”

Benedictine Community

It was the first Benedictine community in Scotland, a daughter house of Christ Church Canterbury.

It wasn’t however the first church in Dunfermline as there was a strong probability that an existing Culdee place of worship was extended to form Margaret’s Church of the Holy Trinity, the precursor of today’s abbey.

Thanks to Turgot’s writing, contemporary scholars can construct a picture of Margaret’s life and the final hours before her death and consequently a picture of Dunfermline’s early Church of the Holy Trinity where she was laid to rest.

Turgot, reflecting on Margaret’s final hours wrote, “it was remarkable that her face, which, when she was dying had exhibited the usual pallor of death became afterwards suffused with fair and warm hues, so that it deemed as if she were not dead but sleeping…”

Margaret’s body was interred opposite the altar and the venerable sign of the Holy Cross that she had erected.

Bannatyne Club

In 1842, members of Edinburgh’s prestigious Bannatyne Club were presented with a short extract drawn from the original Registrum de Dunfermelyn: Liber cartarum abbatie Benedictine…

It was a document that gave a clear indication of both Dunfermline’s strategic significance and its symbolic importance as a final resting place for Scotland Royal families.

It read, “The situation of Dunfermlin, within an easy distance of the principal strengths of Scotland and protected from southern invasion by the Scotwater [Firth of Forth].” Dunfermlin continued peculiary a Royal House.

“Its early benefactors were all Kings; and in imitation of its saintly founder, the succeeding Princes of the Royal Family of Scotland for the most part chose it as their place of burial.”

Given their intimate relationship with the abbey, it seems right that Malcolm III and his queen both now lie in Dunfermline, but as the Registrum de Dunfermelyn indicates, they are not alone, as many of Scotland’s kings, queens and important nobles chose this spiritual place too.

Among them are David I, his grandson Malcolm IV, Alexander III and his sons David and Alexander, Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany, and even the mother of William Wallace is believed to be buried here too.

Robert the Bruce

Robert the Bruce, perhaps Scotland’s most celebrated monarch also rests within the abbey as do his wife, Queen Elizabeth and their daughter Matilda. His story is worth retelling.

Following his death, Robert the Bruce was interred before the high altar in 1329 where he lay undisturbed until 1818 when workmen busy with the new church’s construction came across a tomb protected by two large stones.

Inside were the remains of an oak coffin complete with a skeleton encased in thin sheets of lead. Initially unsure of who the occupant was, forensic teams examined the skeleton and found the breastbone cut open and the heart missing.

It was King Robert the Bruce whose heart, at his request, was first taken on Crusade to the Holy Land but is now in Melrose Abbey.

A plaster cast of his skull, which is now on display, was taken before he was once again laid to rest, this time encased in a new lead coffin into which molten pitch was poured to preserve the remains.

Durham Cathedral

It is generally believed that Margaret’s church was only a priory until her son David I elevated it to abbey status in 1128 although it was not dedicated until about 1150.

He installed Geoffrey, Prior of Canterbury as its first Abbot and began work, so reminiscent of Durham Cathedral, on the nave of what is now part of the current abbey church.

However, the Registrum de Dunfermelyn (preface) offers only scant evidence that this was the case.

It points to a document sent by King Alexander I, in 1120 to Radulph, Archbishop of Canterbury that lists a Peter, “Prior of Dunfermlin” among the ambassadors to England.

It also correctly makes the point that the existence of a prior does not preclude the existence of an abbot. It’s a position confirmed by Chalmers in his Historical and Statistical Account of Dunfermline.

For a more detailed archaeological view of Dunfermline Abbey and the preceding Church of the Holy Trinity, the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) provides a more detailed look at the site as it exists today while also considering some of the building work of previous centuries.

King David I

RCAHMS quite clearly confirms that the construction, which overlies the earlier church, belongs in the reign of King David, dating to 1128.

Interestingly it uses more guarded language when referring to the church’s use as a priory. It said, “A priory was apparently established…” It’s an interesting note of caution particularly as Historic Scotland indicates that the church did indeed function as a priory.

RCAHMS also notes the existence of the remains of a 13th century chapel dedicated to St Margaret which was attached to the end of the abbey church and still survives at the east end of the new church.

More Scottish history articles

- Early Scottish monarchs

- Scottish Enlightenment

- Sweetheart Abbey

- Iona Abbey

- History of the University of Glasgow

For many, one of the most exciting parts of today’s visitor experience is that some of the foundation stones of Queen Margaret’s church remain and are visible, through a grating, allowing a tangible connection with one of Scotland’s best-loved royal figures.

Almost as a bonus, a plan, uncovered in 1916 and outlined on the floor of the nave of the later church, gives us a remarkably clear understanding of how the original building would have looked. It shows for example, a nave and square tower with a choir and apse added at a slighter later date.

Edward I’s Army

From Malcolm III’s time, Dunfermline became a popular residence for Scotland’s royal families and certainly by the early 14th century it had grown substantially.

Given the enmity between Scotland and its more powerful southern neighbour, peaceful cloistered life seemed unlikely to continue.

In 1303, during the Wars of Independence, after wintering for some months at the abbey, Edward I’s army destroyed many of its buildings when leaving, sparing only the church.

It was subsequently restored by a resurgent Robert the Bruce, a man growing in confidence and ambition, whose records of the period show the first reference to a royal palace in Dunfermline. Bruce’s son David II was born here in 1323.

Dunfermline Palace grew from what was the original guesthouse in the abbey complex.

There is some evidence to link it to James III, who developed much of Stirling Castle, and James V who was responsible for much of the work at Linlithgow and Falkland Palaces.

Reformation of 1560

Following the religious upheavals and destruction of the Reformation in 1560, when the abbey was rendered, “a mass of ruins,” James VI had a splendid new palace built, above the waters of Lyne, as a marriage gift for his wife Anne of Denmark.

Almost certainly Oliver Cromwell’s army camped here and in 1715 the Old Pretender’s, “wild Highland supporters held high jinks within its decaying walls.”

In 1600, it was the birthplace of their son Charles I, the last king to be born in Scotland.

Following the Union of the Crowns in 1603, the royal focus turned from Scotland to London and the building once again fell into disrepair following a visit by Charles II in 1651, the year of his Scottish coronation.

Original Cloisters

Today the impressive south wall and parts of the refectory of the original cloisters are among the few reminders of this once royal palace.

For the enquiring mind, Dunfermline Abbey offers an almost inexhaustible supply of historical detail: quirky, mundane, informative and fascinating. The list of descriptive adjectives is a long one.

Its beauty is not only its grand grey façade, sparkling stained glass windows or impressive Romanesque nave but also the juxtaposition of old and new.

It’s a living breathing and active church comfortably living side by side with its older and much-respected neighbour.

Historic Environment Scotland – Dunfermline Abbey Visitor Information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the official abbey website.