The Scottish Enlightenment was a golden age that saw a remarkable flourishing of intellectual activity in Scotland.

It was a period, during the latter part of the 18th century, which saw a remarkable flourishing of intellectual activity in Scotland, particularly Edinburgh.

This Golden Age, dated by some scholars to the years between 1730 and 1790, was a time “when reason gained the ascendancy over faith – in Edinburgh as much as in Europe…”

It was Mr Amyat, the King’s Chemist, “a most sensible and agreeable English gentleman who spent a couple of years in Edinburgh” who said,

“Here I stand at what is called the Cross of Edinburgh and can, in a few minutes, take 50 men of genius and learning by the hand.”

Mr Amyat

The cross of Edinburgh that Amyat referred to is the Mercat Cross (Market Cross) which stands close to St Giles’ Cathedral on the Royal Mile.

A casual observer of events could be forgiven for thinking that the Enlightenment was driven solely from the Scottish capital but that wasn’t the case as Glasgow and to a lesser extent Aberdeen had important parts to play too.

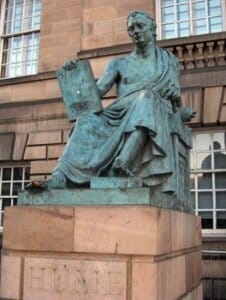

David Hume

The period was crowned by the philosophical brilliance of David Hume and Adam Smith, the father of modern economics.

However, what was remarkable about the Scottish Enlightenment was the broad range of achievements.

It wasn’t just about quantity it was about quality said Professor Sir Tom Devine, Director of Edinburgh University who called it, “in-depth brilliance.”

All the more remarkable considering that in the last dark decade of the 17th century, Scotland had suffered several serious famines.

The country was almost bankrupt thanks to the debilitating effects of the Darien fiasco.

In addition, a number of commentators point to the pervasive influence of the Kirk, an organisation described by historian and broadcaster Melvin Bragg as a “repressive religious society.”

Consider the fate of one young Edinburgh man who angered church authorities.

Thomas Aikenhead was tried for blasphemy following his declaration that theology was a “rhapsody of feigned and ill-invented knowledge…”

Regardless of his subsequent contrition he was condemned and hanged at the Gallowlee in January 1697.

Despite the gloomy picture, there were chinks of light for within 50 years Scotland was a country in the process of change.

With new radical ideas coming from England and the wider continental Europe, the Presbyterian Church became more tolerant and the Jacobite threat faded after their defeat at Culloden in 1746.

Scottish universities embraced the new thinking

The new conditions gave scholars more confidence to reject past authority, make their own decisions and engage, without fear, in scholarly discourse. University students too began to feel the wind of positive change.

Teaching methods improved and the language of instruction moved from Latin to English.

Scottish universities were among the first in Europe to embrace the new thinking of Englishmen John Locke and Sir Isaac Newton.

Tobias Smollett noted that “even the Kirk of Scotland, so long reproached with fanaticism and canting, abounds at present with ministers celebrated for their learning and respectable for their moderation.”

Figures like William Robertson, churchman, historian and Principal of Edinburgh University between 1762 and 1793 epitomised the new moderate approach from the Kirk.

As a member of Edinburgh’s Select Society, established as a debating society, Robertson would have rubbed shoulders with Allan Ramsay, Adam Smith, David Hume and other members of the literati.

Considerable pioneering work was done in Glasgow with the early publication of Francis Hutcheson’s Inquiry into the Originals of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue, in 1724.

Notably, Adam Smith also had a strong association with Glasgow.

He was first a student at Glasgow University later becoming both the Professor of Logic and Professor of Moral Philosophy.

In 1787 he was elected Rector of the University. His best-known work the Wealth of Nations was full of references to the discussions he had with Glasgow merchants.

Aberdeen and the Scottish Enlightenment

The contribution of men from Aberdeen was almost exclusively associated with the town’s two small universities, King’s College and Marischal College.

Prominent in the movement were Thomas Blackwell, Marischal’s professor of Greek and student Thomas Reid.

Reid, a Church of Scotland minister was the founder of the ‘common sense’ school of philosophy and as such he was at odds with the thinking of David Hume whose scepticism he did not share.

As a consequence, he was dubbed, “Hume’s most gifted antagonist within the European republic of letters.” His common sense model was subsequently taught in many of the colleges of North America.

Devine argued that the Enlightenment was not a result of the “civilizing effect of the Union in 1707 but its roots could be found much further back in Renaissance or even Reformation Scotland.”

While, in religious terms, the Reformation brought considerable change to Scotland it also had a significant impact on education.

John Knox’s attempt to introduce a national education scheme was further enhanced in 1696 with the introduction of the Act for Setting Schools. They were systems that ultimately led to an extensive base of literate people.

Was this phenomenon home-grown or did it emerge or was it influenced from abroad?

Most agree that the Scottish Enlightenment was part of a larger Enlightenment movement that encompassed France, Holland, parts of Germany and Italy.

Scotland already had an ancient connection with parts of continental Europe, forged through trade, education and cultural pursuits.

Scottish students travelled to France and Germany for instruction in law and divinity, to Leyden in Holland for medicine and to the eternal city of Rome for the study of art and architecture.

Many Scots embraced and learned from the European Enlightenment experience.

Edinburgh Medical School

Some of the period’s best-known figures took this continental journey before returning to Scotland to continue their work.

For example, Robert Adam studied in Rome and Alexander Monro, who was hugely influential in the establishment of the world-famous Edinburgh Medical School, studied in Leyden.

There was, in return, an admiration of the Scottish model and an acknowledgement from continental thinkers that Scotland, a country with a population of only 1.1 million, was punching above its weight.

The philosopher Voltaire one of the leading lights of the French Enlightenment wrote, “We look to Scotland for all our standards of civilisation.”

University of St Andrews

The Scottish universities were fundamental to the new movement although strangely St Andrews, home to the country’s oldest university, rarely made an impact.

Although worthy of mention is the poet Robert Fergusson, known to have Jacobite and anti-unionist opinions, who studied but didn’t graduate from St Andrews University.

Despite his death at a young age, Fergusson was celebrated in some circles. His friend Frederick Gunion described him as the “Laureate of that city [Edinburgh].”

Scottish Enlightenment: best-known figures

Of course, this new thinking was not confined to the ‘geniuses’ of the period but spread throughout Scotland’s educated classes.

Within this group are people like Adam Ferguson now considered the founder of modern sociology,

Hugh Blair whose study of rhetoric and literary language was particularly influential in the United States and philosopher and economist Dugald Stewart.

In addition, James Hutton who, although originally destined for a career in the law, is now recognised as the founder of modern geology; chemist James Black and William Cullen, a hugely influential teacher of clinical medicine.

It’s impossible also to ignore James Watt whose work with the steam engine became the driving force of the Industrial Revolution.

You have to add architects Robert and James Adam to this extensive list, particularly Robert the designer, to James Craig’s plan, for parts of Edinburgh’s New Town including the delightful Charlotte Square, today the venue of the city’s international book festival.

Continuing with this artistic theme the Enlightenment was the time of the great Scottish portrait painters, particularly Sir Henry Raeburn and Allan Ramsay.

Sir Walter Scott

Some might tentatively include Sir Walter Scott in this illustrious group although his working life lay outside the recognised Enlightenment period.

He was, if not a part of the phenomenon, certainly a product of it, having been educated at Edinburgh University where one of his teachers was Dugald Scott, the biographer of Adam Smith.

Some of his work, particularly the Waverly novels, was inspired by the Enlightenment principles of history and society.

He filled the novels with a sense of romantic nationalism, setting the tone for 19th century literary fiction.

By 1790, there were between 200,000 and 250,000 people of Scot’s birth or descent living in the United States.

Although it’s impossible to tell how many of them were imbued with the spirit of Enlightenment, a proportion of them probably was.

The Scottish Enlightenment Effect on America

What was the Scottish Enlightenment’s effect on America?

Although there may not be a definitive answer to that question there is considerable evidence that several of America’s founding fathers and other important figures of the time were influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment.

Certainly, James Madison, the architect of the federal constitution was exposed to Enlightenment ideas, particularly those of David Hume, at what is now Princeton University by his teacher John Witherspoon a Church of Scotland minister and product of Edinburgh University.

James Wilson, born in 1742, was educated at the University of St Andrews and may also have briefly studied at Glasgow at the time that Adam Smith was Professor of Moral Philosophy.

Wilson, like many Scots of his generation, left his homeland to settle in America. In his luggage were some books ‘borrowed’ from university libraries.

American Declaration of Independence

Initially employed as a tutor in the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania), Wilson became one of the signatories to the American Declaration of Independence.

Benjamin Rush said, “The two years I spent in Edinburgh, I consider as the most important in their influence upon my character and conduct of any period in my life…

” perhaps there is at present no spot upon earth where religion, science and literature to combine more to produce moral and intellectual pleasures than in the metropolis of Scotland”

We know John Adams was an admirer of Hume and turned to Adam Smith’s A Theory of Moral Sentiments to understand how behaviour was socially driven.

Also, Benjamin Franklin was a friend of both David Hume and Adam Smith and freely socialised with the literati when he visited Edinburgh.

Scottish Enlightenment and the President of the United States

Iain McLean from Oxford University (Centre for Jefferson Studies) in a paper, Scottish Enlightenment influence on Thomas Jefferson’s book-buying looks at what influence the Scottish Enlightenment may have had on the third President of the United States.

McLean takes a broad approach to the subject, acknowledging that, “Occasionally one of the American founders makes a definite claim to have been influenced by a certain writer. But these claims are rare.”

While an analysis of Jefferson’s library is a step too far for this short article it’s quickly apparent that his collection covered an impressive range of subjects including, “a substantial Scottish Enlightenment component as of 1783.”

Although Adam Smith and David Hume were featured, the Scottish works which seemed to interest him included literary criticism, poetry and agriculture.

During Thomas Jefferson’s time at William and Mary in Virginia, he was introduced to Enlightenment thinking by William Small who came to America from Scotland to take up the post of Professor of Natural Philosophy.

Jefferson’s classes included ethics, rhetoric, and belles letters. Interestingly Small also taught John Page, the three-time Governor of Virginia while also meeting with Benjamin Franklin in Williamsburg in 1763.

It seems that on his return to Scotland, he kept in contact with Jefferson and probably Franklin too.

REFERENCES: RESEARCH AND DATA

- David Daiches, Peter Jones, Jean Jones (eds) The Scottish Enlightenment 1730-1790: A Hotbed of Genius (Saltire Society), 1996.

- T M Devine (ed), The Scottish Nation 1700-2000, The Enlightenment (Allen Lane, Penguin Press, 1999) pp 29, 65-82, 144, 500.

- Alexander McCall Smith, A Work of Beauty: Edinburgh (Historic Environment Scotland, 2016) pp 20, 129, 168, 193, 215.

See also: further reading

- Adam Smith Works: Adam Smith’s Enlightenment World.

- Stanford University: Scottish Philosophy in the 18th Century.

- Edinburgh World Heritage: Enlightenment Edinburgh

- National Library of Scotland: The Scottish Enlightenment.

- University of Edinburgh: Alumni in History David Hume (1711 – 1776)