The Edinburgh Improvement Act 1867, was designed to address the overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in parts of Edinburgh’s Old Town.

The act authorised the creation of a new body, the Edinburgh Improvement Trust, which was tasked with implementing various urban renewal projects particularly in the Old Town.

Ultimately, it played a significant role in shaping the Old Town’s appearance today.

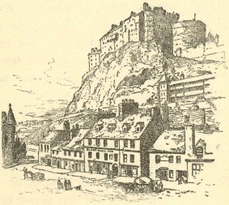

Today thousands of visitors flock to Edinburgh’s Old Town to explore its most popular visitor attractions. But turn the clock back to the second half of the 19th century and you’ll find much of the city’s population living in grim conditions.

Edinburgh Improvement Act 1867: introduction

“An Act for the Improvement of the City of Edinburgh, and constructing new, and widening, altering, improving, and diverting existing Streets in the said City; and for other Purposes. [31st May 1867.]”

“Whereas the Houses in various Parts of the City of Edinburgh have been built in such a manner and are now so old that they have become inconvenient and insalubrious, and are at the same Time so densely inhabited as to be highly injurious to the Health of the Inhabitants…”

Edinburgh Improvement Act 1867

The Edinburgh Improvement Trust

The Edinburgh Improvement Trust was a key body created as part of the 1867 Act to oversee and manage the urban renewal projects aimed at transforming Edinburgh’s decaying Old Town. It played a critical role in implementing the provisions of the act.

Slum clearance

- The trust oversaw the demolition of numerous dilapidated tenements in areas like the Cowgate and Canongate and other parts of the Royal Mile. This clearance aimed to address the overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions that had developed over decades.

Construction of new streets

- Chambers Street: A major thoroughfare connecting the Old Town to the New Town, Chambers Street was constructed to facilitate better access and traffic flow.

- Jeffrey Street: This street was also established to improve connectivity between the Royal Mile and surrounding areas, enhancing pedestrian and vehicular movement.

Improvements in sanitation and drainage

- The trust implemented new drainage systems throughout the Old Town to improve sanitation. This included the installation of modern sewerage systems that helped prevent flooding and reduce the spread of disease.

Public Health Initiatives

- The trust focused on creating healthier living environments by ensuring that newly developed areas had adequate ventilation, light, and sanitary facilities, thus addressing the public health crises of the time

Preservation of historic structures

- Although many buildings were demolished, efforts were made to preserve significant historic sites. The trust worked to maintain and upgrade important buildings, such as St Giles’ Cathedral, ensuring they remained part of the city’s heritage.

Preservation of historic structures

Key figures involved in Edinburgh’s urban renewal:

- William Chambers, the Lord Provost of Edinburgh at the time, was one of the main driving forces behind the improvements. He was a reform-minded politician who saw the need for updating the city’s infrastructure to improve public health and living standards. Chambers had a keen interest in improving housing conditions and championed the redevelopment plans.

- Dr. Henry Duncan Littlejohn (1826–1914) was a prominent Scottish physician and public health official. As Edinburgh’s Medical Officer of Health and also a professor of forensic medicine at the University of Edinburgh, he was instrumental in the city’s efforts to improve public health during the 19th century.

- Patrick Geddes (1854-1932) was a Scottish biologist, sociologist, and urban planner. He is considered one of the founders of modern urban planning and is known for his holistic approach to city development

- David Cousin (1809-1878) was a prominent Scottish architect and town planner. By the time the 1867 Edinburgh Improvement Act was passed, Cousin had already been involved in various significant town planning and architectural projects in Edinburgh.

- David Lessels (1823–1886) was a prominent Scottish civil engineer who played a key role in the urban development and modernisation of Edinburgh, particularly in connection with the Edinburgh Improvement Act . Lessels was appointed as the chief engineer for the Edinburgh Improvement Trust,

Under the Improvement Act, Cousin and Lessels, according to Historic Environment Scotland planned St Mary Street (previously St Mary’s Wynd), Blackfriars Street, Jeffrey Street and Chambers Street, a street named after the aforementioned William Chambers.

Interestingly, St Mary’s Wynd has a well documented place in Edinburgh’s history. It was along this narrow thoroughfare that James IV and his army progressed on their way to the Battle of Flodden in 1513.

Related reading on Truly Edinburgh:

- Places in Edinburgh connected to Sir Walter Scott

- People and places connected to Adam Smith in Edinburgh

- Magdalen Chapel: Old Town Landmark

- Edinburgh’s royal attractions

The 1861 Census highlighted the dreadful conditions in Edinburgh’s Old Town.

Only a few years before the Improvement Act, the 1861 Scottish Census highlighted some of the dreadful conditions in Edinburgh’s Old Town.

In addition to the census data, the publication, in 1865, of Henry Duncan Littlejohn’s Report on the Sanitary Conditions of Edinburgh in 1865 added further damming statistics.

- This article on Truly Edinburgh has more information: The 1861 Census: awful conditions in Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Grassmarket

Who lived in the Old Town?

Although working class and poorer families made up much of the population it was also home to craftsmen and tradespeople.

Over the years several of Scotland’s best known historic figures also had an address in the Old Town. Among them were:

- Sir Walter Scott was born in Edinburgh’s Old Town in 1771, in College Wynd, and though he later moved to the New Town, his early life and literary work were deeply influenced by the history and atmosphere of the Old Town.

- James Boswell, the biographer of Samuel Johnson, was born and raised in Edinburgh’s Old Town, where he lived in Blair’s Land near the Cowgate, immersing himself in the intellectual and social life of the city.

- David Hume, the renowned philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment, lived in Edinburgh’s Old Town in James Court, where he wrote much of his influential work and engaged with the city’s vibrant intellectual community.

- Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, lived and worked in Edinburgh’s Old Town at Panmure House, where he wrote and refined his seminal work, The Wealth of Nations.

Edinburgh’s New Town

By the mid-19th century, the exodus of people from Edinburgh’s Old Town to the New Town was well underway.

It was driven by huge differences in living conditions and social aspirations. The New Town, with its spacious Georgian architecture, wide streets offered a sharp contrast to the overcrowded, dilapidated tenements of the Old Town.

This article on Truly Edinburgh has more information: Edinburgh New Town: symbol of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Scottish Enlightenment and Edinburgh’s urban reform

Although the Scottish Enlightenment period had ended around half a century before the Edinburgh Improvement Act came into force, scholars have looked for connections between them

Consequently many have argued that the Edinburgh Improvement Act and the Scottish Enlightenment are linked in a number of ways. The Act’s focus on urban renewal, public health, and social improvement reflects the Enlightenment’s values of reason, progress, and human improvement. Adam Smith and David Hume might well have agreed.

“No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable.”

Adam Smith

Edinburgh Improvement Act 1867: suggestions for further research & reading

- Smith, P.J., 1989. The rehousing/relocation issue in an early slum clearance scheme: Edinburgh 1865-1885. Urban Studies, 26(1), pp.100-114.

- Smith, P.J., 1994. Slum clearance as an instrument of sanitary reform: The flawed vision of Edinburgh’s first slum clearance scheme. Planning Perspectives, 9(1), pp.1-27.

- Morris, R.J., 2013. White Horse Close: Philanthropy, Scottish Historical Imagination and the Re-building of Edinburgh in the later Nineteenth Century. Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, 33(1), pp.101-128.

Vancouver