Traquair House sits in the beautiful Scottish Borders in an ancient landscape of forests and woodland.

It is the oldest inhabited house in Scotland and has had a royal connection since Alexander I came to hunt wild boar in 1107.

But Traquair House is more than just another historic house, it’s a symbol, a reminder of Scotland’s turbulent and bloody past. “It’s a house of lost causes, a house of memories, or simply the most romantic house in Britain.”

Twenty-six other Scottish kings and queens have stayed, some welcome some not. One of the early royal visitors who stayed at Traquair was William I (the Lion) who arrived in 1176.

It was from there that he signed the charter that authorised Joceline, Bishop of Glasgow to found a Bishop’s burgh on the banks of the Molindiner.

This bestowed all the privileges that the king’s burghs were entitled. This burgh grew to be the city of Glasgow.

Death of Alexander III

On a stormy night in Fife in 1286, the future of Scotland was dramatically changed when King Alexander III was killed. With his death and the intervention of Edward I of England, the long and brutal Wars of Independence began.

Border houses were strengthened against the marauding English and Traquair House was incorporated within a fortified tower as part of a defensive line of castles and towers spreading along the River Tweed.

In 1478 it was bought by the uncle of King James III, the Earl of Buchan for the paltry sum of 70 Scots Merks (approximately £3, 75p)

With the dawning of the 16th century, James Stuart the first Stuart laird prepared plans for enlarging the house but died in the bloodbath that was Flodden Field

However, before the work started he was succeeded by a son and four grandsons who gradually extended the house.

The fourth laird was Sir John Stuart who served as captain of the bodyguard to Mary Queen of Scots and her son who became James VI of Scotland (I of England).

The young queen visited the house in 1566 with her husband Lord Darnley and her baby son James.

In the King’s Room on the first floor of the house, her state bed is still covered by a hand-stitched quilt said to have been worked by Mary and her ladies-in-waiting. At the foot of the bed sits a cradle used by the future king.

With the support of Charles I, John Stuart the seventh laird became Lord High Treasurer of Scotland and later Commissioner of Scotland and in 1628 he became the 1st Earl of Traquair.

His increasingly powerful position in Scotland brought him vastly increased wealth.

This enabled him to add a top floor to the building fearing the nearby River Tweed would overflow and cause flooding changed its course to take it further from the house.

His good fortune however didn’t last very long. He was given the impossible task of mediating between the Scots and Charles I as he attempted to introduce the English form of worship in the Scottish Kirk.

Traquair’s relationship with the king soured and as riots raged on the streets of Edinburgh he confided to the Marquis of Hamilton his doubts over the new Anglican service.

Many Scots were outraged at the attempt to force a new form of worship on them and gathered in thousands in their towns and villages to demand that Charles change his mind.

Traquair House: National Covenant

Leading Scottish Presbyterians drew up a document of protest against the actions of the king called the National Covenant. On February 28 1638 Scottish nobles gathered at Greyfriars Church in Edinburgh to sign the document

As a staunch supporter of the Royalist cause, Traquair found life at the house very dangerous.

After a series of victories against Covenanting forces, the king’s general in Scotland, the Marquis of Montrose headed to the Borders unaware that forces led by General David Leslie were also heading south to meet him.

Montrose badly needed men and Traquair sent his son Lord Linton and 600 Peeblesshire horse to join him.

Battle of Philiphaugh

The ensuing battle of Philliphaugh (1645) has gone down in history as one of needless savagery with many of the Royalist camp women and children being slaughtered by the victorious Covenantors.

The defeated Marquis fled from the battlefield and in the words of John Buchan, “Did not draw rein until he reached the old house of Traquair, whose grey and haunted walls still stand among the meadows where the Quair burn flows to the Tweed.”

The earl perhaps aware that the covenanting army was not far behind refused to open the door.

He was later accused of treachery but in the dangerous days of the 17th century, it was surely a matter of self-preservation.

Traquair was subsequently dismissed from his post, fined heavily and it was said that he spent his last days begging on the streets of Edinburgh.

Traquair House: Catholic tradition

The Catholic traditions of the family, which remain today, were started by John, the second earl who in 1649 married Lady Henrietta Gordon the daughter of John Gordon, the second Marquis of Huntly.

But for marrying a Catholic he was fined £5000, (an enormous sum in those days) and given a ‘temporary term of ‘imprisonment’.

It was a short marriage, lasting only a year until Henrietta’s death. His second wife was also a Catholic and it seems a very determined lady.

She was Lady Ann Seton who even after her husband’s death was determined to bring up her children as practising Catholics which was strictly against the law.

Mass was said for the family and other local Catholics in a small room on the upper floor. A narrow stair, which led out of a hidden cupboard, provided a handy escape route for the resident priest and in later years Jacobite refugees.

Peebles mob

There is some documented evidence of harassment because of their faith, records show that a mob from nearby Peebles attacked the house and some “Papish trinkets” were taken and destroyed.

Apart from this minor incident, the Stuart home remained virtually untouched despite the family’s support for Catholicism and the Jacobite cause.

Whatever the rights or wrongs of their political and religious philosophy the Stuarts were a family who “supported Mary Queen of Scots and the Jacobite cause without counting the cost. They were imprisoned, fined and isolated for their beliefs.”

It was not until the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 that the family could practise their religion without fear of prosecution. The present chapel at Traquair dates from that time.

The third Earl of Traquair died young and was succeeded by his brother Charles who became the fourth earl.

He was a faithful supporter of King James II (who had converted to Catholicism) and was subsequently imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle, a suspect in a Jacobite plot.

The present family at Traquair are descended from the fourth earl’s daughter Catherine.

Traquair House: Prince Charles Edward Stuart

Prince Charles Edward Stuart, a visitor to the old house in 1745, left through the ‘Bear Gates’ heading for his final defeat at Culloden.

The fifth earl promised the gates would remain locked until a Stuart once again sat on the throne of Scotland.

The gates guarded by two ‘sullen’ bears remain firmly closed to this day and visitors to the house enter the grounds by a side gate.

The accounts for the construction of the famous gates still exist. They show £12.15s for building the pillars and £10.4s for carving the bears, also included are four gallons of ale for the workmen.

Related articles

- Jedburgh Abbey

- Dryburgh Abbey

- Melrose Abbey

- Smailholm Tower

- Day trip from Edinburgh to the Scottish Borders

With the Jacobite cause lost, life became quieter at Traquair. The fourteenth laird who was the eighth and last earl died in 1861 as the house was slowly being modernised.

It was first opened to the public in 1952 several years before electricity was installed

Peter Maxwell Stuart the twentieth laird who worked tirelessly to develop and promote the house was also recognised in the USA.

A framed document that hangs in a prominent place in the house came from the city of Baltimore which presented him with honorary citizenship says, “In recognition of your distinguished achievements to the life of our times…” It is dated 1975.

Today the house is crammed with evocative memories. In the Museum Room among the significant treasures are a fading mural painting dated about 1530. This was discovered under the wallpaper.

A rosary and crucifix, belonging to Mary Queen of Scots still catches the sunlight on a ledge by the window.

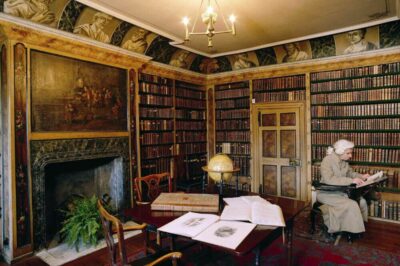

There are two libraries, now restored to their eighteen-century appearance. They have a collection of books numbering around 3000.

In one of the ‘modern wings’ the Dining Room displays the best of eighteenth and nineteenth century furnishings and paintings.

The house, home to the Stuarts of Traquair has not been bought or sold since 1491 and few documents have been discarded.

There are I’m sure many ‘gems’ waiting to be discovered by an archivist who works with today’s custodian of this historic building, the twenty-first lady laird Catherine Maxwell Stuart.

Traquair House visitor information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the official website.

Traquair House: suggestions for further research & reading

- Chester, C., 1998. Traquair. British Heritage, 19(6), pp.40-45.

- Laing, D., 1859, November. Inventar of Popish Trinkets, gotten in my Lord Traquair’s House, Anno 1688; All solemnly burnt at the Cross of Peebles,’with some remarks. In Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Vol. 2, pp. 454-457).

- Poleg, E., 2013. The earliest evidence for anti-Lollard polemics in medieval Scotland. Innes Review, 64(2), pp.227-234.

- Archives, T.H., 2015. Letter (Holograph) from Henry, Cardinal Duke of York to Charles Stuart, seventh Earl of Traquair, 7 November 1795. Traquair House,‘A Jacobite Story, Traquair’s Jacobite Connection.