William Chambers, born 16 April 1800, was a writer, publisher, social reformer, Lord Provost of Edinburgh and much more besides.

In 1882, the year before his death, William Chambers published a short autobiography, more a series of reminiscences, which he called – A Long and Busy Life.

Rarely has there been a more apt title for a man who packed so much into his 83 years.

William, spent his early years in the Scottish Borders town of Peebles with his father James, a successful cloth manufacturer, his mother Jean and five siblings. Among them was his brother Robert who would play an important part in his life.

William Chambers: education in the Scottish Borders

He painted a bleak picture of his education in Peebles, saying that “In the schools, I passed through, there was not a map, nor a book on geography, or history or science…”

It was a simple and cheap arrangement, diversified with boisterous outdoor exercises and a certain amount of fighting…”

It was the local library that came to the rescue of both William and Robert giving them the opportunity to immerse themselves in the classics of English Literature.

A set of the Encyclopedia Britannica, bought by their father, allowed them some insight into science and an old globe introduced them to geography.

William spoke also of overhearing the intellectual conversations of his father and his acquaintances, often sparked by articles in the Edinburgh Review.

He said, for example, I remember the interest we took in the account of the exertions of Sir William Herschel, in forming his famous telescope… which led to his discoveries in the planetary world.”

By the time William had reached the age of 13, poor economic conditions, created in no small measure by the Napoleonic War, forced James Chambers into bankruptcy.

Desperate for work, the family moved to Edinburgh.

Their tenement flat in the capital was in, “a second-rate street home to other families of limited means.” It was a far cry from their Peebles home, one that William called, “a pleasing little mansion.”

William Chambers: apprentice bookseller

Determined to work in the world of literature, William was apprenticed to bookseller John Sutherland of Calton Street in May 1814 – a strict disciplinarian by all accounts.

In the following five years, he worked hard not only to learn his trade but to develop an entrepreneurial spirit that would serve him well in later years. All this while continuing a rigorous program of self-education.

Even as a young man working in Edinburgh, the continuing Napoleonic War cast a shadow over life and William often made reference to it in his writing.

While he quite naturally wrote of the great victory at Waterloo in 1815, and the “immense public rejoicings,” he noted also that it was, “the end of a frightful and protracted effort, that had loaded the country with an almost unendurable amount of taxation.”

The unfairness of taxation, particularly its effect on the working class was a subject he often returned to. But perhaps most of his ire was directed at the hated Corn Laws not repealed until 1846 and abolished three years later.

With his apprenticeship finally over he opened his first bookshop in May 1819 – an open-air stall really – but the first step in the world of business.

It was close to a similar venture started by his brother Robert.

No story about this remarkable man is complete without saying a little about his brother.

While Robert’s life deserves much more than a few short lines, there are a number of notable literary successes to mention, some as part of a brotherly partnership but others in his own name.

Early in his career, he tried his hand at both poetry and prose before following the same path as Sir Walter Scott and writing on Scottish subjects, particularly those inspired by history.

For example, Traditions of Edinburgh (1824), a wonderful work packed with memories, stories and of course Edinburgh traditions, was an immediate success and was the work that established his reputation.

It remains today an indispensable source of information for anybody with an interest in Scotland’s capital city.

In 1844, fearing an adverse reaction, he anonymously (initially) published the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation which presented an account of the history of the Earth, from the solar system to the origins of mankind.

While it sold well, reactions were polarised – from approval to outright damnation.

Charles Darwin called it, “that strange unphilosophical but capitally-written book” while revealing that some people had suspected him of being the writer.

Sadly, despite this and other literary successes, Robert Chambers is today a much-neglected author.

Gazetteer of Scotland

Over the years William too wrote and published a wide range of material, including, the Book of Scotland, an examination of the pre-Union Scottish Government and the Gazetteer of Scotland with his brother.

But the publication, produced with the support of his brother, that eclipsed them all in terms of popularity was the Chamber’s Edinburgh Journal which first appeared on 4 February 1832.

It was the first British example of a cheap weekly publication and its huge success eventually led to the establishment of W and R Chambers, today part of a much larger publishing house.

While 1832 saw the birth of the Journal it also saw the death of Sir Walter Scott, a man who had often supported the brothers as they forged a path in the publishing world.

It was a poignant moment for them as they joined the other mourners at Dryburgh Abbey, the most beautiful of the four great Border abbeys.

The following year he married Harriet Seddon of Westminster, London. Sadly, none of their three children survived.

William travelled extensively, often to gather material for future writing projects.

Among the many ports of call were – England, Italy, Switzerland and France.

He even crossed the Atlantic to Canada and the United States in 1853, where he spoke warmly of his reception at the White House and his meeting with President Franklin Pierce.

The following year he published an account of that trip, Things as they are in America.

Thanks to these excursions he has left a collection of wonderfully evocative anecdotes full of meetings with royalty, presidents, prime ministers and ‘Scotchmen’ and women who had made their mark in a foreign land. And on very rare occasions, a glimpse into his private life.

William Chambers: Lord Provost of Edinburgh

While not abandoning his writing, he turned to politics because “the citizens of Edinburgh were in want of a Lord Provost and to my surprise fixed on me for the distinguished office.”

By this time Chamber’s concerns about the appalling living conditions in Edinburgh were already deep-rooted. He had developed a reputation as a reformer, and a promoter of model housing, and workers’ cooperatives.

He was also a contributor, with his Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Old Town of Edinburgh,to the Poor Law Commission’s extensive inquiry into the living conditions of the working class.

There were unsurprisingly many previous hard-hitting descriptions of just how wretched the conditions in the wynds and closes of the Old Town were during the mid-19th century.

One report came from Edinburgh surgeon Alexander Miller.

His damming account concluded that, “The dwellings of the poor are generally very filthy in their interior…

“those of the lowest grade often consist of only one small apartment, always ill ventilated both from the nature of its construction and from the densely peopled and confined locality in which it is situated…”

More famous Scots in history

The Act of Improvement of the City of Edinburgh

Chambers was elected to the office of Lord Provost in 1865.

Although his workload must have been wide and varied, his tenure was marked by one particular piece of legislation –The Act for the improvement of the city of Edinburgh (1867) which legislated for the clearance of over 30 separate slum areas within the Old Town.

As part of the process of change, it would be wrong not to mention the highly respected Henry Littlejohn, Edinburgh’s first Medical Officer of Health who worked closely with the provost.

It was his report, presented to the Council in 1865, which highlighted the association between poverty, overcrowding, poor sanitation and poor health.

It was the precursor to the new legislation.

Interestingly there are some academics who argue that without the combination of Littlejohn and Chambers, Edinburgh Town Council might have wasted the opportunity.

Before any change could be realised, Chambers, with officials in tow, had visited every close, every wynd and every tenement, an exhausting process for a man not in the best of health. His preliminary plan, which followed, led to an intense period of public discussion.

Many of the ratepayers who attended meetings were overwhelmingly against the project because of the cost.

there were also concerns that the demolition of dwellings would go ahead without proper plans to replace them.

In saying this it was clear during the early stages of planning that William Chambers and Henry Littlejohn both had a vision of new housing suitable for those displaced.

The fact that this did not happen to any great extent could well be laid at the door of what are often called ‘competing interests.’

Between 1868 and 1875 over 2,700 houses were demolished but only 350 new ones were constructed and some were designed for skilled artisans which pushed the rent beyond poorer families.

By the time William Chambers became Lord Provost, Edinburgh not only had an Old Town but a New Town too. George Drummond a previous incumbent of the post, often considered the ‘founder of modern Edinburgh’ was a man who dedicated his life to improving living conditions in the city.

Edinburgh Royal Infirmary

He helped establish Edinburgh Royal Infirmary in 1738 and five chairs of medicine at the University of Edinburgh

But he is best remembered as the driving force behind Edinburgh Town Council’s decision to approve the 1767 plans for the spacious streets, elegant squares and gardens of the New Town.

As important as this was in the expansion of Edinburgh, it did little or nothing to alleviate the dreadful Old Town conditions.

The medieval St Mary’s Wynd, originally named after a Cistercian Convent dates to around 1335 and lies close to the Canongate, part of the Royal Mile. It was one of the first areas to be redeveloped.

Substantially demolished as part of the improvements it was replaced by the considerably wider and less crowded St Mary’s Street, still part of the Old Town landscape today.

Although the ancient bricks and mortar have now long gone, some of the fascinating history of the wynd remains – the buildings and their occupants, the people who plied their trade and those who simply passed this way.

For example, the progress of James IV and his army, along St Mary’s Wynd on the way to the Battle of Flodden in 1513, was well documented.

As was, following his terrible defeat, the section of the defensive Flodden Wall, built in fear of an English invasion of Edinburgh.

Robert Chambers writing in the Traditions of Edinburgh (1824) noted, “Bothwell [third husband of Mary Queen of Scots] endeavoured to get out of the city by leaping a broken part of the town wall in Leith Wynd, but finding it too high was obliged to rouse once more the porter at the Netherbow…. They then passed down St Mary’s Wynd.”

At the end of his first term as Lord Provost, some of the work remained unfinished so he chose to run again. Successfully re-elected, he continued with his work but only for a short period following a decision by the Town Council to abandon the project.

William resigned from his position and retired to private life. That he couldn’t complete the project remained a matter of huge regret to him throughout the rest of his life.

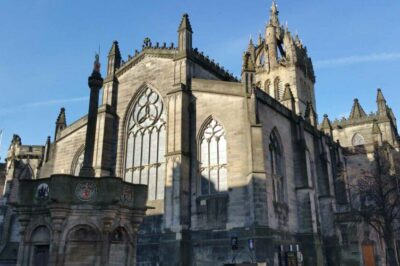

William Chambers: St Giles’ Cathedral

Without his public duties to perform, William Chambers turned his attention to what he called the “discreditable condition” of St Giles’ Cathedral, one of the town’s most prominent and important buildings.

With reminders of pre-Reformation Edinburgh and an English attack of 1385 still clearly visible in the aisles, Chambers set about an ambitious restoration project, much of it paid for with his own money.

Sadly, he died on 20 May 1883, only a few days before the kirk was due to reopen. The first religious service to be held in the newly refurbished building was the funeral of William Chambers.

Although he had purchased and extensively renovated the estate of Glenormiston near Peebles in 1849, he was buried in Peebles at the site of the original St Andrew’s parish church.

Of the new wider streets created in the Old Town – Chambers Street – today the home of the National Museum of Scotland was named in William’s honour. It’s also the site of a bronze commemorative statue of the former Lord Provost. Its low base with bronze reliefs depicts, Literature, Liberality and Perseverance.

Greyfriars Bobby

Nearby is another statue with often forgotten connections to William Chambers – Greyfriars Bobby. This little Skye Terrier, as the story goes, guarded his master’s grave in Greyfriars Kirkyard until his death.

Touched by the story, Chambers a director of the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, arranged to pay for Bobby’s license to save him from being taken by the dog-catcher and destroyed.

While William had refused a knighthood from Prime Minister William Gladstone, he accepted a baronetcy and although he never lived to receive it, it was surely a fitting tribute to a long and busy life.