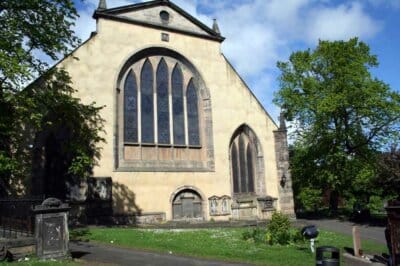

St Giles’ Cathedral takes pride of place on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, its famous crown steeple dominating the Old Town skyline. This magnificent building has become one of Edinburgh’s top attractions.

For over 900 years St Giles’ Cathedral has watched over the city in silent witness as the history of Scotland unfolded on its doorstep.

There is no more evocative place to visit in Edinburgh.

Today a visit to the Cathedral will give you the opportunity to quietly absorb the incredible atmosphere of the building and remember the people who created its history.

Quick facts about St Giles’ Cathedral

- St Giles’ was destroyed in 1385 when an English army attacked Edinburgh

- The statue of John Knox guards the entrance.

- King David I founded the Cathedral in 1124.

- In 1745, the arrival of Bonnie Prince Charlie in the city was announced in the Cathedral.

- Regular concerts and other events are held there.

- Despite its name, it is not a cathedral. It has a Church of Scotland congregation which worships according to the Presbyterian tradition. All faiths are welcome to attend.

St Giles’ Cathedral’s history

There was a Christian church in Edinburgh as early as 854 belonging to the Bishopric of Lindisfarne (modern Northumberland, England). However, a church that stands where St Giles is now, may not have been established until the early 12th century.

Traditionally churches in Scotland were dedicated to Scottish or Irish saints but St Giles was born in Athens around 640 and became the patron saint of lepers, beggars and cripples.

He spent the last years of his life in France where he founded a monastery. Although he died between 720 and 726 it wasn’t until 1562 that his body was moved to Toulouse and buried in the crypt of St Severin.

Sir William Preston of Gorton

It was in the same year that an arm bone said to belong the venerated saint was brought to Edinburgh by Sir William Preston of Gorton and presented as a gift to the church.

Historians are unsure why he was chosen but St Giles was popular in many Catholic countries including France with whom Scotland has had a long relationship.

In 1385, an English army under Richard II crossed the border to avenge an attack by the Scots the previous year. On his way north to the capital the Border abbeys of Melrose and Dryburgh were burned.

“Edinburgh, was given to the flames and nothing spared of the town.” Little remained of St Giles when the fire finally burned out, only the entrance porch, a part of the choir, nave and the base of the spire were spared.”

J Cameron Lees

Work began in 1387 to rebuild the church and the provost of the burgh hired three masons to begin the reconstruction.

The contract stipulated that they were to build five chapels with pillars, vaulted roofs and “lighted with windows.” Unlike the original building, which was roofed with wood, the craftsmen were instructed to ensure that the new construction was “thekyt with stane”

Over the next 150 years, building work continued and a considerable number of other chapels were added by the craftsmen’s guilds of Edinburgh. At one point there were nearly 50 altars in the church.

A Papal Bull announced further change for St Giles’. A year after the king confirmed collegiate status for the church in a charter signed in Stirling an announcement was “Given at Rome at St Mark’s in the year one thousand four hundred and sixty seven…” The church was henceforth called the Collegiate Church of St Giles of Edinburgh.

It retained this status for less than a century when the Reformation, one of the most tumultuous periods in Scotland’s history, swept away the old religious order.

The jurisdiction and authority of the Pope in Scotland were abolished and the celebration of Mass forbidden.

The Protestant Confession of Faith was accepted as “hailsome and sound doctrine grounded on the infallibill trewth of godis word.”

Death of Mary of Guise

After the death of Scotland’s Queen Regent, Mary of Guise in 1560, her daughter Mary Queen of Scots returned to Scotland from France in August 1561 to claim her throne. She found the new Protestant order was well established.

It was a daunting task for the young Catholic queen to return to a country and face her subjects so implacably opposed to her religious beliefs.

Links with John Knox

St Giles is inextricably linked with John Knox, a towering figure in Scottish history and widely regarded as the father of the Scottish Reformation.

This firebrand preacher became minister of St Giles’ (1559-1572) and spent much of his tenure delivering sermons denouncing Mary with unrelenting hostility.

His workload was immense he was said to have preached twice on Sundays and three times every other day of the week.

The Reformation also brought physical change to the building. With the new order, there was a determination to sweep away all the signs of the old ways.

The large number of altars, which had been built, were ripped out with the help of sailors from the Port of Leith.

Gold, silver and other valuables were catalogued and removed. Even the arm bone of St Giles was stripped of its silver mountings and discarded in the rubbish.

All the “through stanes” or tombstones were taken out and the interior was whitewashed. It must have seemed an austere and desolate place with all its finery gone.

In 1633, sixty one years after the death of Knox, Charles I arrived in Edinburgh for his belated Scottish coronation and with plans to Anglicise the Scottish form of worship.

A new diocese was created by the king and the church was ‘erected’ to cathedral status. “As decent and fitt for a churche of that eminencie.”

The civic authorities were prepared to take further measures to ‘please’ the king.

They sent the Dean to Durham in the north of England, to make a drawing of the inside of their cathedral “In order to fit up and beautify the inside of St Giles in the same manner.”

It soon became clear however that the attempt by the king to introduce the English prayer book into the Scottish Kirk would not be tolerated.

Legend tells us of the protest of Jenny Geddes a herbwoman at the nearby Tron Church as she attended the new service at St Giles in 1637.

“Daur ye say mass in my lug”

Jenny Geddes (legend)

The National Covenant and Greyfriars Kirk

Jenny csreamed as she hurled her stool at the unfortunate Dean of Edinburgh, driving him from the pulpit.

It was perhaps the first weapon perhaps, in the coming English civil war and the start of a chain of events that would end in the death of Charles at the hands of the public executioner.

A ‘symbolic’ stool remains on display as a reminder of the events of that day.

Demonstrations continued and two leading Scottish Presbyterians, Moderator of the General Assembly Alexander Henderson and his clerk Archibald Johnston (Lord Warriston) drew up a document of protest against the actions of the king.

The National Covenant, as it was called, was signed at nearby Greyfriars Kirk.

It underlined the Covenaters’ hostility to Roman Catholicism and bound the signatories to the defence of God and the king, providing that the interests of the law and church came before the king’s.

A copy of what is undoubtedly one of Scotland’s most important historical documents remains in St Giles’.

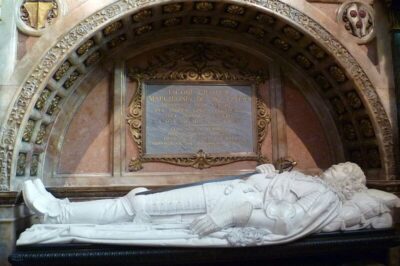

One of the first to sign the Covenant was James Graham, the Marquis of Montrose, who later changed sides and became the king’s general in Scotland.

After a string of remarkable victories against Covenanting forces, he was finally defeated at Philliphaugh near Selkirk.

He was executed at the Mercat Cross and his head put on a spike outside the Cathedral, other parts of his body were dispersed around the country.

When Charles II came to the throne in 1660, the remains of Montrose were returned to Edinburgh and buried in St Giles’. His memorial stands in the Chapman Aisle.

It is perhaps ironic that on the opposite side of the Cathedral stands the memorial to Archibald Campbell, the Marquis of Argyle perhaps the greatest of Montrose’s enemies.

From time to time the building has also been used for secular purposes.

Offices for town officials, a school and a prison were all accommodated in space behind a wall built between the Kirkyard door in the south to the north kirk door at the Stynkand Style.

Even the Maiden (Edinburgh’s guillotine) was stored there when not in use.

1707, Treaty of Union

After protracted negotiations, on 16 January 1707, the Treaty of Union was ratified and Scotland ceased to be an independent country.

It’s a date that remains uppermost in the minds of many Scots.

Daniel Defoe better known as the writer of Robinson Crusoe was a spy, working in Edinburgh for the English government. He noted that the service held in St Giles’ to commemorate the occasion was attended by “a very great congregation, where was present many members of parliament…”

On 1 May of that year, as the Treaty came into effect, the citizens of Edinburgh listened as the bells rang out to the tune of Why should I be so sad on my wedding day.

After the failed Jacobite uprising and their defeat at Culloden Moor in 1745, the “history of Scotland becomes very dull and that dullness extends to the annals of St Giles…an air of gloom and depression pervaded the city.”

By 1758, a new minister was in place. Dr Hugh Blair became one of the most popular preachers to grace the pulpit. His speeches and sermons were translated into many European languages.

“Men of taste and letters”

“Men of taste and letters” flocked to the church to listen. Robert Burns was often among the congregation.

Dr Samuel Johnson, the renowned English writer and lexicographer, said of Blair “though the dog is a Scotchman and a Presbyterian and everything he should not be I was the first to praise him… I love Dr Blair’s sermons.”

By the beginning of the 19h century, the fabric of the building had deteriorated badly.

It was in a poor state of repair and in 1829, the government made a grant to the city authorities of £12,600 for the restoration of the building. The architect appointed was a now notorious William Burn.

What followed said one former minister was “deplorable and can scarcely be conceived by those who have not themselves seen what was done. The three inner chapels on the south of the nave with the re-vestry, south porch, and part of the Holy Blood Aisle were cut off…

“All the niches outside the building with the rich canopies were swept away. The picturesque roof “theikit with stane disappeared.” It was wanton and needless destruction.

William Chambers

Former Lord Provost of Edinburgh, (1865-69) William Chambers said “so much for Mr Burn’s improvements on St Giles… fortunately the spire escaped his attentions.”

It was that same Lord Provost that came to the rescue. William Chambers and his brother Robert had come to the city as young men to seek a better life.

They made their name and fortunes as writers and publishers and their company still flourishes today.

They both loved the city and William, as Lord Provost had been responsible for modernising great swathes of the overcrowded and unsanitary Old Town.

It was this civic pride that persuaded him to try and undo the dreadful work of Mr Burn.

Together with an excellent architect and backed by overwhelming public support for the ambitious project,

Chambers by then an old man and in declining health was determined to see the High Church fully restored.

On a spring day in 1883, he came to see the work that was nearing completion. “I never could have believed that the interior was so fine,” he said. It was to be his last visit.

By 23 May 1883, the restoration was complete and a public service was held. Over 3000 people filled the building. But it was too late for William Chambers, he had died three days earlier.

In his sermon, the minister reminded the congregation that “so long as these stones remain one upon another, will men remember the deed which William Chambers hath done and tell of it to their children.”

Thistle Chapel

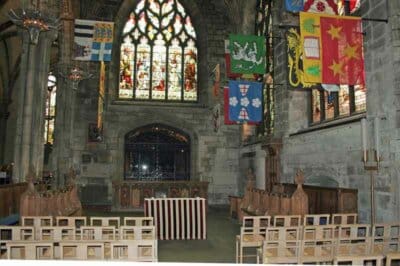

A statue of John Knox guards the entrance, sternly watching as the many visitors who throng this ancient place stop to stare up at the vaulted roof and magnificent stained glass windows.

Many also visit the exquisite Thistle Chapel the spiritual home of the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle and wonder at its exquisite wood carvings.

The Order’s original chapel was situated in the nave of Hollyrood Abbey after James VII revived the Order in 1688. But as anti-Catholic feelings in Edinburgh grew, the chapel was ransacked and the Order was left without a home.

It wasn’t until 1906 that a new home was found when the Earl of Leven and Melville left funds for the building of a new chapel which was inaugurated by King George V in 1911.

Robert Louis Stevenson

In the south aisle there is a tribute to one of Scotland’s best-loved literary figures, a relief sculpture of Robert Louis Stevenson cast in bronze by American Augustus St Gaudens.

The strains of Bach or Handel can often be heard coming from the magnificent Rieger organ during lunchtime and evening recitals. The church also welcomes visiting choirs and musicians from around the world.

Restoration work still continues. A message from the present minister reminds us “These old stones could be clean again and draw tomorrows people to seek and find a faith for celebrating good things and find comfort in times of difficulty.”

Visiting St Giles’ Cathedral

The historic building is crammed with countless treasures to explore so leave plenty of time to make sure you see everything you want to.

If you’re on your first visit to Edinburgh, remember you may not get the opportunity to come back again, so it would be a shame to miss anything.

Highlights:

- The exquisite Thistle Chapel, with its detailed neo-gothic woodwork and stunning gold-leaf ceiling, is home to the Order of the Thistle an order of Scottish chivalry.

- In the south aisle, there is a tribute to one of Scotland’s best-loved literary figures, a relief sculpture of Robert Louis Stevenson cast in bronze by American Augustus St Gaudens.

- A look in the quiet darkened corners will remind visitors of the role of our armed forces in more recent wars. Tattered colours starkly remind us of the horrors of Ypres, Malta, Sicily and other far-off places.

- Enjoy the amazing views over the city and discover the ancient wooden interior of the clock tower with the rooftop tour.

Where is St Giles’ Cathedral?

The High Kirk of Edinburgh is situated on the High Street part of the Royal Mile which lies at the heart of Edinburgh’s Old Town.

It lies close to Edinburgh Castle, with the Palace of Holyroodhouse only a short walk away..

If you’re walking and that’s the best way to get around Edinburgh, it’s less than a mile from Waverley Station.

It’s an uphill journey and the streets are crowded in the summer so leave a bit of extra time to get there.

There is no public parking but you can be dropped off fairly close to the entrance. There are some mobility issues inside the building so check before you go.

Further visitor information

For information on opening hours, cost of entry and other tips to help you plan your visit, go to the cathedral website.